When Your Spine Feels Less Than Fine: Common Spinal Pathologies

Posted on 2/7/19 by Laura Snider

As much as we would all prefer to stay young forever, we’re only human...and our human bodies age. Our bones, tendons, joints, and ligaments experience pressure, strain, and degradation as time passes.

This is especially true for the bones and cartilage of the spine. It isn’t a coincidence that we typically think of older people as having “bad backs”— the spine does a lot of work to support the rest of the body, and it can experience a great deal of wear and tear after years of faithfully doing its duty. Cartilage doesn’t stay stretchy and cushiony forever. Thus, osteoarthritis and problems with the intervertebral discs become more common with age.

In this post, we’re going to talk about a few frequently-occurring spinal pathologies, their causes, and what methods doctors often use to treat them.

Cervical Spondylosis: A Literal Pain in the Neck

Did you know that about 85% of people over the age of 60 are affected by cervical spondylosis? This condition, sometimes referred to as (osteo)arthritis of the neck, can be asymptomatic, but most of the time it is characterized by pain and stiffness in the neck. This pain can range anywhere from mild to severe, and headaches or popping sensations in the neck can also occur.

Cervical spondylosis is largely caused by degeneration that occurs with age. Thus, this is a condition that mostly affects people who are middle-aged or older.

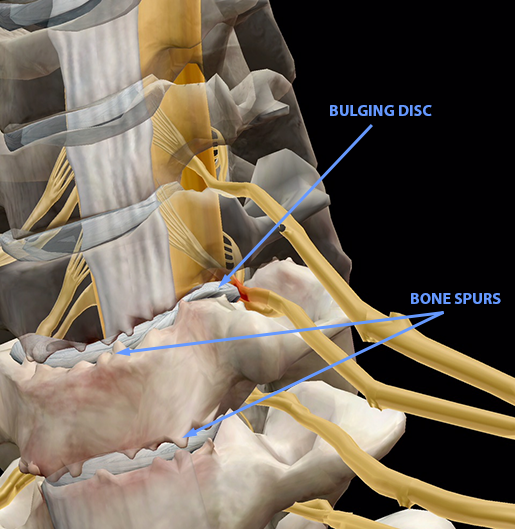

Over time, the cartilaginous discs sitting between the vertebrae lose height; that is, their squishy centers dry out and they can bulge or become herniated. If disc degeneration causes vertebrae to become too close to one another, bone spurs can form. Increased pressure on the facet joints of the spine can also cause inflammation characteristic of arthritis.

Image from Muscle Premium.

Image from Muscle Premium.

Though symptom severity does vary, cervical spondylosis is a natural part of aging. That makes it pretty difficult to avoid. Fortunately, it can be treated without surgery most of the time. Physical therapy exercises can often help relieve pain and restore range of motion. Patients sometimes wear a soft collar/neck brace for short periods of time to immobilize the cervical spine enough to allow for recovery. Pain and inflammation can also be managed with medication, ice, heat, and/or steroid injections, as directed by a medical professional.

Bone Spurs: Fighting the Good Osteo-fight

The formation of bone spurs is a prime example of how your body’s strategies for responding to conditions like cervical spondylosis are not always as helpful as intended. As connective tissue in the spine begins to degrade, bones can start making contact with one another. In an effort to relieve the resulting pressure and pain, small protrusions called osteophytes grow on the bones.

Image from Muscle Premium.

Image from Muscle Premium.

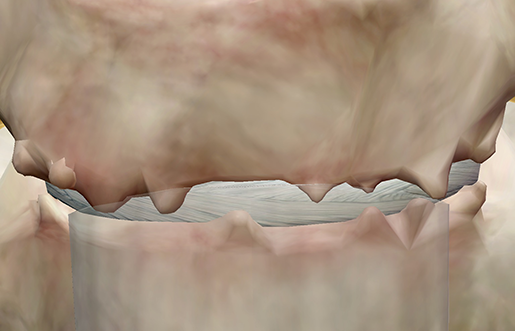

If a spinal disc is sufficiently degraded, osteophytes that form on one vertebra can fuse with osteophytes on an adjacent vertebra in a misguided attempt at restoring spinal stability and easing pain. These are referred to as “kissing osteophytes,” though there is nothing nice or affectionate about them.

Bone spurs can go unnoticed until they start to cause problems such as interfering with nerves, reducing the mobility of joints, or even compressing the spinal cord itself. Medication and ice are often used to manage pain caused by bone spurs. Surgical removal is sometimes necessary for especially problematic bone spurs.

Intervertebral Discs: Breaking It Down

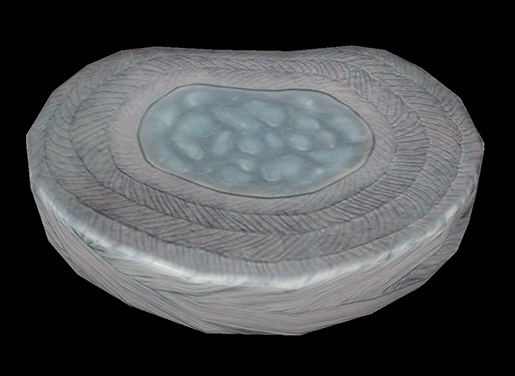

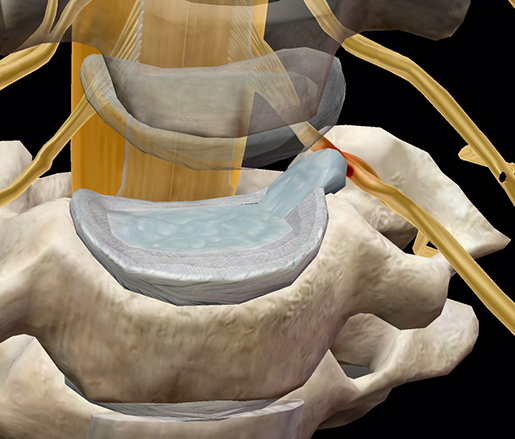

There are several kinds of disc issues that can occur either independently or under the umbrella of cervical spondylosis. However, before we talk about these, let’s familiarize ourselves with the structure and composition of a healthy intervertebral disc.

The discs in the spine are kind of like Junior Mints: they have a solid structure on the outside and a gooey center on the inside.

Image from Muscle Premium.

Image from Muscle Premium.

The ring-shaped outside part is called the annulus fibrosus, and it is made up water and layers of flexible collagen fibers. The blueish center is the nucleus pulposus, composed of water and proteins called proteoglycans. There are also two thin layers of cartilage, called endplates, that sit between the bony vertebrae and the discs above and below. As a unit, each intervertebral disc provides shock absorption and aids mobility by keeping the vertebrae from scraping up against each other.

Notice how much water there is in those discs? With age, discs start to dry out and their nuclei become less gelatinous. The layers of collagen on the outside also start to lose their lovely organized structure. Urban & Roberts 2003 compared a healthy disc to a degenerated one in their study, and the differences in the nucleus and annulus are clear. Take a look at the image here.

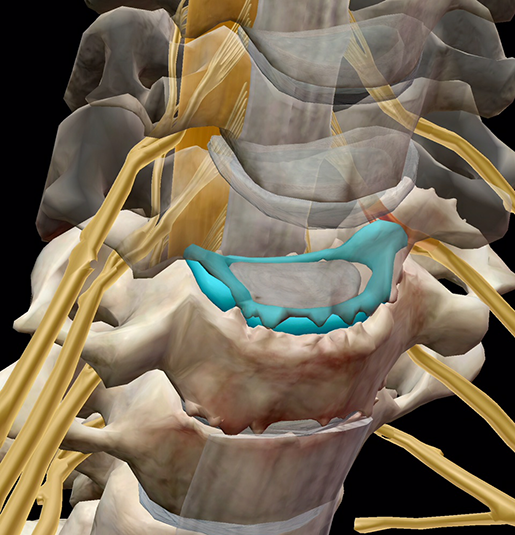

A collapsed disc can result from this breakdown of structure and elasticity in the annulus and loss of fluid in the nucleus. The collapsed disc on its own does not necessarily cause symptoms — it is only when the disc in question restricts the space available to spinal nerves or causes vertebrae to touch that further problems arise.

One way in which a collapsed disc can cause a problem is if it bulges: that is, the annulus is pushed outward but doesn’t break. In the image below, the highlighted disc is collapsed and the annulus is pushing on a nerve root. The vertebrae on either side of the disc are also so close together that bone spurs (the little spiky bits at the edges of the bones) have formed.

Image from Muscle Premium.

Image from Muscle Premium.

If the annulus does break either fully or partially, pushing the material of the nucleus outward instead, the resulting condition is known as a herniated or slipped disc.

Herniated disc. Image and video footage from Muscle Premium.

My fellow twenty-somethings, you’re not off the hook when it comes to disc problems. Although bulging and herniated discs often occur as a result of overuse, aging-related wear and tear, or some combination thereof, they can also be a result of acute trauma from a fall or auto accident.

Bulging and herniated discs usually take a couple of weeks to heal, with medication and ice typically used to deal with pain (heat is often used in place of ice after the first few days of treatment). Rehabilitation exercises assigned by physical therapists usually focus on strengthening back and abdominal muscles to help support the spine. Surgery is not typically necessary.

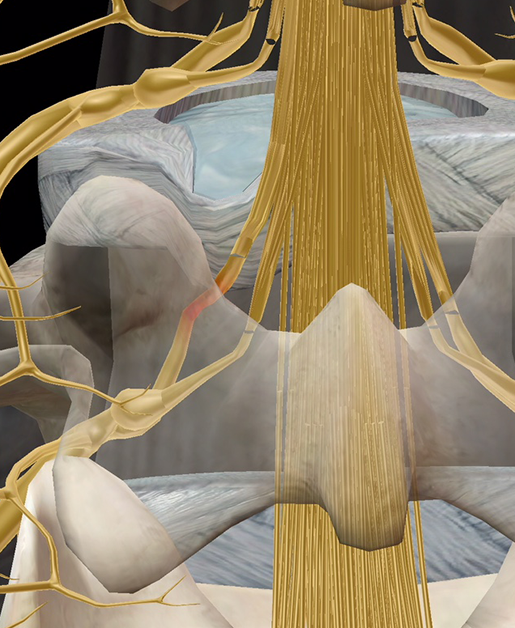

Sciatica: Those Discs Are Getting On My Nerves!

As the images in the previous sections show, both bulging and herniated discs can put pressure on nearby spinal nerve roots, interfering with their innervation of muscles and tissue. This can cause pain, tingling, and/or numbness in those muscles or tissues, and is generally referred to as radiculopathy. In general, the lumbar and cervical portions of the spine suffer radiculopathy more frequently than the thoracic spine.

That brings us to sciatica, a pinching of the sciatic nerve. The sciatic nerve is the largest nerve in the body, extending from the lumbar spine down to the thighs. When there is pressure on its root, sharp pain can shoot down the back of one leg. Sudden motion can aggravate this pain, and in some cases even walking and standing can become difficult.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

The image below shows a bulging disc squeezing one of the sciatic nerve’s roots.

Image from Muscle Premium.

Image from Muscle Premium.

Since sciatica usually involves a bulging or herniated disc, it probably won’t surprise you to know that pain-relieving medication, ice/heat, and strengthening exercises are frequently involved in the treatment process.

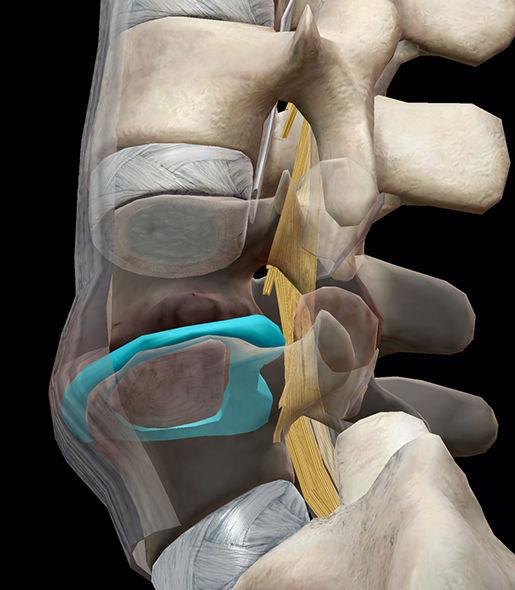

Spinal Stenosis: Under Pressure

The conditions discussed above can sometimes cause a narrowing of the spinal canal called spinal stenosis. This can also occur as a result of injury, especially if vertebrae are fractured or dislocated.

Much like disc issues, spinal stenosis is more frequent in the cervical or lumbar spine. The image below shows how a bulging disc in the lumbar spine can intrude on the space meant for nerves. In this case, it’s pushing on and displacing the cauda equina, the bundle of nerves that makes up the bottom of the spinal cord.

Spinal stenosis overview. Image and video footage from Muscle Premium.

Spinal stenosis overview. Image and video footage from Muscle Premium.

Symptoms of spinal stenosis depend on which area of the spine is affected. Lumbar stenosis typically involves back pain in the lumbar region as well as weakness, numbness, or tingling in a leg or foot. Cervical stenosis can involve weakness, numbness, or tingling in a hand, arm, leg, or foot, as well as neck pain. Walking or balance problems are also possible, and in severe cases, incontinence and/or urinary urgency may occur.

Non-surgical treatment for spinal stenosis follows a similar pattern to treatment for bulging or herniated discs. In specific cases of lumbar stenosis in which there is a thickened ligament in the back of the spinal column, percutaneous image-guided lumbar decompression (PILD) is a possible method of treatment. PILD involves removing pieces of the thickened ligament, but does not require general anesthesia.

If symptoms of spinal stenosis become particularly severe or disabling, surgery may be required. There is a range of possible procedures, but the general goal of stenosis surgeries is to create space within the spinal canal, relieving the pressure in the affected area.

Even if the aging process can't be stopped, it's always a good idea to support your spine just as it supports you (aww). Maintain balanced strength in the muscles of your back and abdomen, follow safety guidelines for heavy lifting and other strenuous activities, and try to use good posture even if you sit at a desk for work.

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you a professor (or know someone who is)? We have awesome visuals and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.

Additional Sources: