What Makes Lyme Disease Tick

Posted on 6/2/23 by Sarah Boudreau

Here in the northern hemisphere, the weather is warming up and summer is right around the corner. Kids on school vacation are frolicking outside with their friends, adults are welcomed outside by sunny skies… and ticks carrying Lyme disease are ready to feast.

About 20,000 cases of Lyme disease are reported in the United States every year, making it the country’s most common vector-borne disease. It’s most common in the northeastern and north midwestern states.

The disease was discovered when, in 1975, Yale researchers were notified about a cluster of pediatric arthritis cases in the small town of Lyme, Connecticut. The disease was initially called “Lyme arthritis” before other symptoms like neurological problems were discovered.

In this blog post, we’ll explore what Lyme disease is, how it’s diagnosed and treated, and what the future looks like for the disease.

What is Lyme disease?

Lyme disease is caused by Borrelia burgdorferi, a type of spirochete. Spirochetes are a group of bacteria that are so tightly coiled they look like tiny springs—the bacteria that causes syphilis is also a spirochete. Lyme disease can also be caused by the bacteria B. mayonii, but this happens rarely.

B. burgdoferi. Photo by Janice Haney Carr, accessed through CDC's Public Health Image Library.

B. burgdoferi. Photo by Janice Haney Carr, accessed through CDC's Public Health Image Library.

B. burgdorferi is spread by the blacklegged tick, also known as the deer tick. The ticks are infected at the larval or nymphal stages when they feed on an infected host, typically a small rodent. When an infected tick bites a human, the bacteria is transmitted.

A female blacklegged tick. Photo by Jim Gathany, accessed through CDC's Public Health Image Library.

However, the tick must be attached to its host for 36-48 hours for the bacteria to take hold. Removing a tick within 24 hours can greatly reduce the likelihood of getting Lyme disease. This is easier said than done—nymphal ticks are about the size of a poppyseed, and ticks like to bite areas where they may not be detected, like the groin, armpits, and scalp. Many people with Lyme disease aren’t even aware they’ve been bitten by a tick.

Stages of Lyme disease

Lyme disease presents in three stages.

The early localized stage occurs 3-30 days after the tick bite. During this time, a rash develops called erythema migrans. Erythema migrans will expand over the course of several days, reaching up to a foot in diameter, and it typically has a distinctive “bulls-eye” appearance. 70-80% of people with Lyme disease will develop erythema migrans. However, erythema migrans can be more difficult to identify on darker skin. Many believe that this is because reference materials and medical textbooks show erythema migrans almost exclusively on light skin.

Erythema migrans on light skin. Photo via CDC's Public Health Image Library.

In addition to erythema migrans, symptoms during the early localized stage include aches, swollen lymph nodes, fever, chills, fatigue, and headache.

In the early disseminated disease stage, the disease spreads to other parts of the body. This occurs 3-12 weeks after infection. Patients in this stage experience symptoms such as:

- Neck stiffness

- Muscle pain

- Dizziness, headache

- Fever

- Irritability, depression

- General malaise

Cardiac problems are rare, but complications like atrioventricular blocks and myopericarditis sometimes occur. Roughly 20% of patients’ central nervous systems are affected, causing conditions like cranial nerve neuropathy and meningitis. About 5% of patients develop Bell’s palsy, a neurological disorder that causes paralysis on one side of the face.

If left untreated, late disseminated Lyme disease occurs months or even years after the initial tick bite and subsequent infection. Many develop Lyme arthritis, which occurs when the bacteria enters joint tissue, causing inflammation and pain. In addition to arthritis and other joint pain, symptoms include:

- Insomnia

- Brain fog and problems concentrating

- Dizziness and vertigo

- Migraines

Lyme disease diagnosis and treatment

Diagnosing Lyme disease is often difficult: most symptoms overlap with other diseases, and Lyme disease’s trademark “bulls-eye” rash doesn’t occur in all cases. Early treatment is key, but testing for Lyme disease can be tricky. Most Lyme disease tests don’t look for bacteria, they look for the antibodies the immune system produces to combat the bacteria. Antibodies need several weeks to build up before they can be detected, which means that people with early localized Lyme disease can receive false negative results. When it comes to cases that involve the central nervous system, a patient’s cerebrospinal fluid may be taken in order to diagnose the disease.

Lyme disease is treated with antibiotics—usually doxycycline, amoxicillin, or cefuroxime. These antibiotics are typically taken orally, but sometimes they are delivered intravenously in neurologic cases and in cases with late Lyme arthritis.

Most cases are cured by two to four weeks of antibiotics, but sometimes patients experience post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome (PTLDS). With PTLDS, patients experience fatigue, pain, and cognitive symptoms more than six months after treatment is finished. The cause of PTLDS is not clear: B. burgdorferi may trigger an autoimmune response, the Lyme disease infection may be more difficult to detect, or maybe PTLDS is caused by something other than Lyme disease.

According to a study published by Johns Hopkins Medicine Lyme Disease Research Center in 2022, about 14% of patients who were diagnosed and treated early for the disease developed PTLD.

The future of Lyme disease

The active season of blacklegged ticks is expanding. Due to climate change, the warming climate in the ticks’ American range means that they are more active earlier in the spring and later in the fall. Luckily, new vaccines are being developed to protect against this serious disease.

Before we talk about the future of Lyme disease vaccines, let’s talk about LYMErix. Developed in the 1990s, LYMErix was the only FDA-approved vaccine for Lyme disease. It was delivered over the course of three shots, and it was about 75% effective in reducing risk in adults during clinical trials. However, bad press and anti-vaccine sentiment made vaccine sales plummet—despite the fact that the FDA and CDC did not find a higher incidence of serious side effects among the vaccinated. The manufacturer voluntarily pulled LYMErix from the market in 2002.

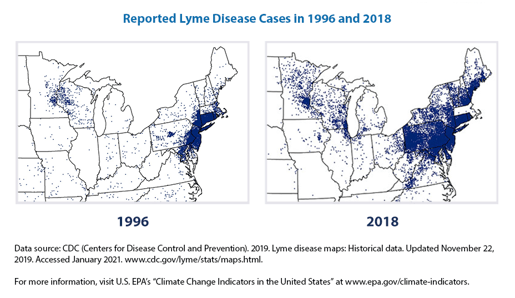

Fast forward to today: Lyme disease is more geographically widespread and affects about a half a million people in the United States every year.

Graphic showing the increase of reported Lyme disease cases. Graphic via the Environmental Protection Agency.

Lyme disease is considered more of a threat than it was twenty years ago. Let’s take a look at three projects that are currently in progress:

- Pfizer and Valneva’s vaccine is in phase 3 trials with the hopes of releasing it to the market in 2025. The vaccine causes the immune system to create antibodies that block a protein on the surface of the bacteria, stopping it from leaving the tick. This vaccine is delivered over three doses.

- MassBiologics’s shot is technically not a vaccine. It targets the same protein as Pfizer and Valneva’s vaccine, but instead of causing the body to produce antibodies, this shot cuts out the middleman and delivers a protein to bind to the bacteria’s surface. It’s delivered through an annual dose.

- Yale University’s vaccine takes a different approach: their mRNA vaccine makes it harder for ticks to feed. When the body recognizes the tick’s saliva, the skin becomes redder, making the tick more visible and therefore more likely to be removed promptly. In trials on guinea pigs, the ticks aren’t able to feed as aggressively, and they detach themselves earlier.

Read more

Want to read more? Here are some posts on the Visible Body Blog we think you’ll like.

- Flu Vaccines Are Nothing to Sneeze At

- What We Know—And Don’t Know—About Long COVID

- Endometriosis: A Common but Misunderstood Disorder

- 5 Deadly Pandemics of the Past and What We Can Learn From Them

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you an instructor? We have award-winning 3D products and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.