What Is Heart Valve Disease?

Posted on 2/22/21 by Laura Snider

Valentine’s Day may have come and gone, but seeing as February is National Heart Month we’ve got another circulatory system blog post for you! In the past, we’ve talked about common cardiovascular conditions, as well as stroke and heart disease.

Because today (February 22) is Heart Valve Disease Awareness Day, our spotlight will be on heart valve disease, which is a category covering a number of conditions that impair the function of any of the heart’s four valves. We’ll talk about what the heart’s valves do, the various ways in which they can malfunction, and some of the most common heart valve conditions.

What do the heart's valves do?

Let’s start with a brief overview of the four valves in the human heart. In general, the purpose of the heart’s valves is to keep blood flowing in the correct direction. They open to allow blood to pass from one chamber to another, or from the heart into the pulmonary trunk and aorta, and close to prevent backflow.

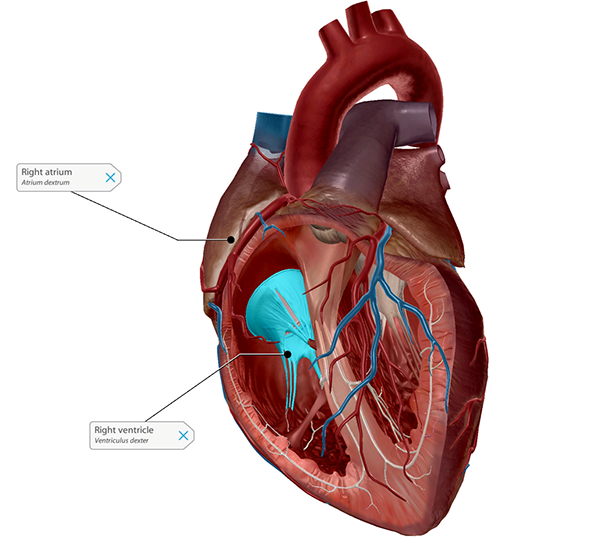

Deoxygenated blood from the body enters the heart through the right atrium. Then, it passes through the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle.

The tricuspid (right AV) valve connecting the right atrium and right ventricle. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

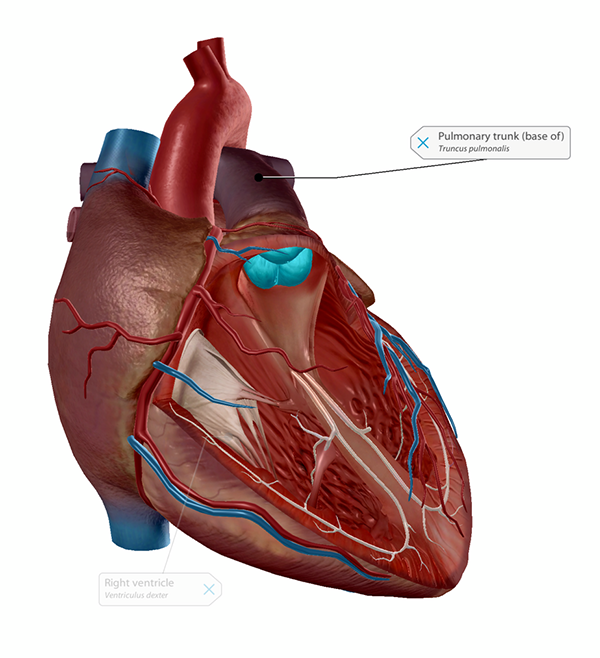

Blood from the right ventricle moves into the pulmonary trunk through the pulmonary semilunar valve.

The pulmonary valve connecting the right ventricle to the pulmonary trunk. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

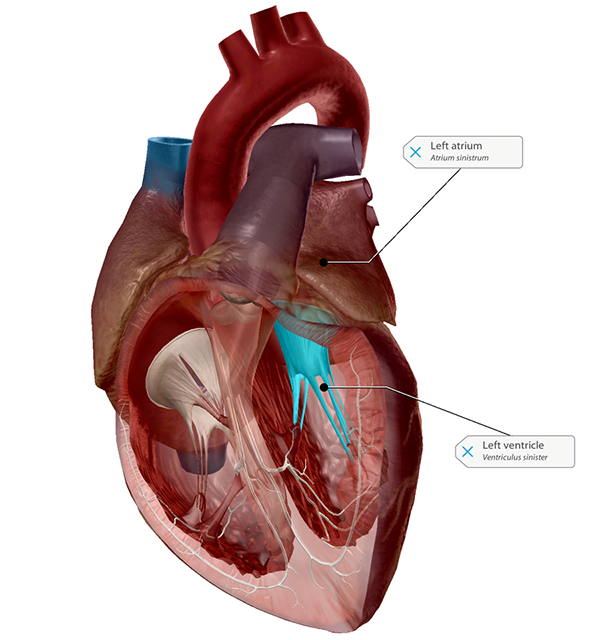

Once that blood has gone through the pulmonary loop and is freshly oxygenated, the pulmonary veins deposit it in the left atrium. It passes through the mitral (bicuspid) valve to get to the left ventricle.

The bicuspid (left AV, mitral) valve connecting the left atrium and left ventricle. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

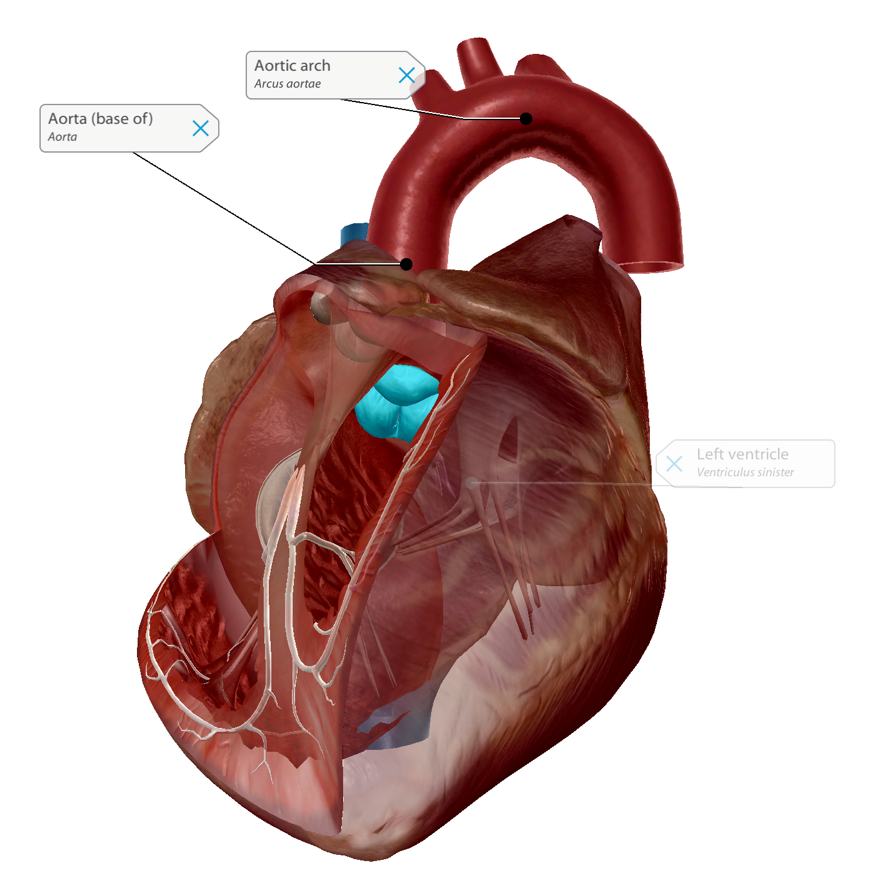

Finally, oxygenated blood leaves the heart through the aorta after passing through the aortic valve.

The aortic valve connecting the left ventricle and aorta. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

As you saw in the images above, the tricuspid and mitral (bicuspid) valves separate the heart’s atria from its ventricles. For that reason, these valves are referred to as the atrioventricular (AV) valves. The pulmonary and aortic valves are also called the semilunar valves because their leaflets are shaped like half-moons.

The two phases of the cardiac cycle—systole and diastole—and the paired “lub-dub” sounds of the beating heart can be described in terms of the opening and closing of these valves. Systole is when the ventricles contract, pushing blood out of the heart through the semilunar valves. It begins with the closing of the AV valves and ends with the closing of the semilunar valves. The AV valves closing is the first sound in the heartbeat. Diastole is when the ventricles relax and blood flows from the atria to fill them again. It begins with the closing of the semilunar valves and ends with the closing of the AV valves. The semilunar valves closing is the second sound in the heartbeat.

The heart’s valves opening and closing as the heart beats. Video footage from Physiology & Pathology.

The heart’s valves opening and closing as the heart beats. Video footage from Physiology & Pathology.

What happens when the heart's valves don't work properly?

There are two main issues that arise when heart valves aren’t functioning properly.

The first is regurgitation, or the backflow of blood. If one of the valves doesn’t close all the way, some blood can leak back through the partially-open valve into a previous chamber. Symptoms of valvular regurgitation can include shortness of breath, cough, fatigue, heart palpitations, lightheadedness, and swelling of the feet and ankles.

Stenosis is the other problem that can arise with heart valves. Essentially, it means that the valve can’t open all the way, so the full amount of blood can’t get where it needs to go. This can lead to symptoms such as chest pain, shortness of breath, fatigue, dizziness, and fainting.

Risk factors for heart valve disease include (but are not limited to) congenital heart defects, infection of the heart tissue, and hardening or degeneration of valves due to aging.

Sometimes, problems with the heart’s valves can be severe without causing noticeable symptoms, so make sure to get regular checkups and always let your healthcare provider know if you’ve noticed any changes to your cardiovascular health.

Common heart valve conditions

Regurgitation and stenosis can happen on their own or together, and they can technically occur in any valve. However, some valves are more commonly affected than others.

Mitral valve prolapse (MVP)

Mitral valve prolapse, or MVP, is a heart valve disorder that occurs in about 2% of the population. It’s also known as floppy valve syndrome, click-murmur syndrome or Barlow’s syndrome.

In cases of MVP, the mitral valve (the one that separates the left atrium from the left ventricle) doesn’t close correctly. Part of one or both of the valve’s leaflets collapses and protrudes up into the left atrium, which allows some blood to leak back through.

Mitral valve prolapse and blood flowing back into the left atrium. Video footage from Physiology & Pathology.

Mitral valve prolapse and blood flowing back into the left atrium. Video footage from Physiology & Pathology.

According to the American Heart Association, bursts of rapid heartbeat (palpitations), chest discomfort, and fatigue are common symptoms. Most of the time, MVP isn’t life-threatening, but if there is significant regurgitation, complications such as heart attack, stroke, or arrhythmias may occur.

Aortic stenosis

The aortic valve is the one most commonly affected by heart valve disease. The American Heart Association reports that more than 20% of Americans over 65 suffer from aortic valve stenosis, in which blood flow is restricted by the narrowing of the aortic valve. Common symptoms include fatigue, chest pain, shortness of breath, and a rapid, fluttering heartbeat. Usually, aortic stenosis in older people is caused by calcium buildup and scarring in the valve cusp.

Aortic valve stenosis due to calcium buildup. Video footage from Physiology & Pathology.

Aortic valve stenosis due to calcium buildup. Video footage from Physiology & Pathology.

Aortic stenosis is also possible in younger people, but this is usually because they have a congenital heart defect called a “bicuspid aortic valve.” Normally, the aortic valve has three leaflets, or flaps, but sometimes one is missing or two of them are fused together, resulting in an aortic valve with only two leaflets. This means that the heart has to work harder to pump blood throughout the body. Calcium buildup and stiffening of the valve can lead to aortic stenosis in some cases.

Many times, people don’t know they have a bicuspid aortic valve until later in life, but the complications of this condition can include heart failure, aortic aneurysm, or aortic dissection, so it is important for individuals diagnosed with bicuspid aortic valve disease to work with healthcare professionals to monitor and treat their condition. Around 80% of people with BAVD have surgery to repair or replace the valve.

How is heart valve disease diagnosed and treated?

In addition to a physical exam in which a healthcare provider listens to the heart, there are many different diagnostic tests and imaging options for problems with the heart valves.

These include:

- ECG/EKG

- Chest X-ray

- Echocardiography

- Stress test

- MRI

- Cardiac catheterization

Treatment depends on the type and severity of the particular disorder. Sometimes doctors will prescribe medication to address symptoms. Types of medication used to treat heart valve disease can include those that regulate blood pressure, prevent arrhythmias, treat heart failure, or prevent blood clotting.

As mentioned above, treatment can also include surgery to repair or replace valves that aren’t working correctly.

Want to learn more about cardiovascular pathologies? Check out these related Visible Body Blog posts:

- Physiology & Pathology: Four Common Cardiovascular Conditions

- Atherosclerosis: The Anatomy and Physiology of a (Silent) Killer

- Serious as a Heart Attack: 7 Facts about Cardiovascular Disease

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you an instructor? We have award-winning 3D products and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.

Additional Sources: