VB News Desk: The Double Danger of Measles

Posted on 12/3/19 by Laura Snider

Here in the US, we’ve been hearing about measles outbreaks—and the importance of vaccinating children against measles—on the news for a while. Over the last few weeks, a measles outbreak in Samoa has claimed the lives of 53 people.

Recently, a set of related studies published in Science and Science Immunology, as well as a commentary (also published in Science Immunology) demonstrated how contracting measles can be even more detrimental to the body than previously thought. In addition to causing uncomfortable symptoms and potentially deadly complications, measles also induces “immune amnesia,” essentially erasing the immune system’s memory of other pathogens it has encountered.

Today, we’ll be talking about the results of these studies and why they make it even more important that people get vaccinated against measles. We’ll start with a brief overview of measles and how adaptive immunity usually works. Then, we’ll go into a little more detail on measles-induced immune amnesia.

Measles is highly contagious and can be fatal

Measles resides in the mucus of the nose and throat of infected individuals. This makes it highly contagious via coughing and sneezing. In fact, the “measles virus can live for up to two hours in an airspace where the infected person coughted or sneezed.” Unless they are protected against it with a vaccine, 9 out of 10 people who are exposed to measles will contract it. What’s more, people with measles can spread it to others starting around four days before they develop the characteristic measles rash, and they can continue to spread the disease for around four days after the rash appears as well.

Measles typically begins with these symptoms:

- High fever

- Cough

- Runny nose

- Red, watery eyes

Small white spots (Kolpik spots) may appear inside the mouth 2–3 days after the onset of these symptoms.

Three to five days after symptoms begin, a rash consisting of flat red spots appears, spreading from the head down to the rest of the body. At this point, the fever might spike dangerously high (around 104°F).

Among the complications of measles are such ailments as ear infections and diarrhea, and it only gets worse from there. One out of every 20 children with measles develops pneumonia, which is the leading cause of measles-related death in young children. Measles can also cause encephalitis (brain swelling), which can result in convulsions as well as lasting brain damage.

The immune system remembers

Your body protects itself from disease in two main ways: innate and adaptive immunity.

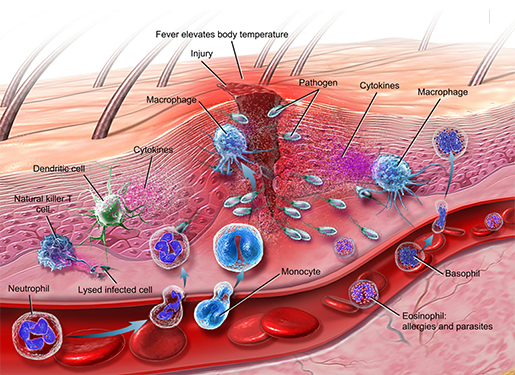

Innate immunity is an all-purpose response, which involves physical defenses (skin, mucous membranes), antimicrobial substances, fever, inflammation, and phagocytes (white blood cells that consume pathogens).

Innate immune response. Illustration from A&P 6.

Innate immune response. Illustration from A&P 6.

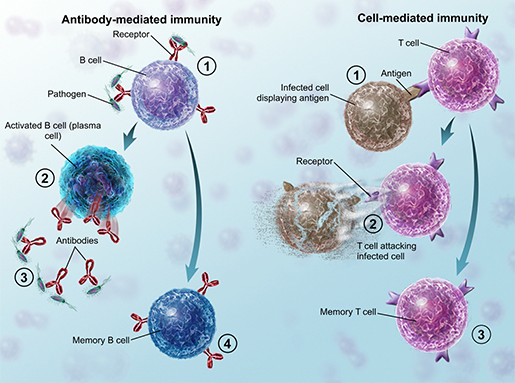

Adaptive immunity is the body’s way of defending itself against particular diseases. Its success depends on the body’s ability to remember previous invaders and engage defenses when it encounters them again.

T and B lymphocytes are two types of white blood cells important to adaptive immunity. B cells produce antibodies (which “tag” foreign substances and microbes). T cells destroy cells that have been infected. After an infection, “memory” B and T cells remain—this is how the body stores information on how to fight off diseases it’s encountered in the past.

Adaptive immunity. Illustration from A&P 6.

Adaptive immunity. Illustration from A&P 6.

Vaccines capitalize on this process and train the immune system without causing illness. For example, when you get the measles vaccine, a weakened form of the measles virus is introduced into your body so the immune system can produce T cells and antibodies. Memory B and T cells remain after this “imitation infection” caused by the vaccine. If a vaccinated person encounters the measles virus again, the immune system can recognize it and knows how to fight it off.

How does measles harm the immune system?

Even after a person recovers from measles, the disease’s effects live on in their immune system. On the positive side, the immune system has adapted to become good at fighting off measles, so a second infection in the same person is unlikely.

The problem is that measles directly infects immune cells (including B and T memory cells), impairing the immune system’s ability to respond to other diseases. That’s essentially what the two recently published studies demonstrated.

The Petrova et al. study (the one in Science Immunology) observed changes in the populations of memory and naïve B cells following measles infection. Ultimately, they found that there was “(i) incomplete reconstitution of the naïve B cell pool leading to immunological immaturity and (ii) compromised immune memory to previously encountered pathogens due to depletion of previously expanded B memory clones.”

The Mina et al. study (the one in Science), reported that “measles caused elimination of 11 to 73% of the antibody repertoire across individuals.” In a press release from Harvard Medical School, Prof. Mina describes the antibody elimination like this: “Imagine that your immunity against pathogens is like carrying around a book of photographs of criminals, and someone punched a bunch of holes in it. It would then be much harder to recognize that criminal if you saw them, especially if the holes are punched over important features for recognition, like the eyes or mouth.”

The fact that measles “punches holes” in the immune system’s memory has a couple of implications. Most importantly, it means that in addition to measles being dangerous on its own, people who have recovered from measles are more susceptible to other types of infections for the next 2–3 years. Because of this, the Mina et al. study suggests that it could be beneficial for people recovering from measles to receive booster shots of routine vaccines like polio and hepatitis.

Ultimately, this means that the measles vaccine is an even more valuable public health tool than previously thought. Vaccinating against measles not only protects you from a potentially deadly disease—it’s also a safeguard for the whole immune system.

A PSA regarding the measles vaccine

Before the advent of the measles vaccine in the 1960s, measles killed around 2.6 million people every year. By 2017, 85% of children around the world received the first dose of the measles vaccine by the time they were a year old.

Measles and its potentially catastrophic effects can be prevented if everyone in the population who can get vaccinated does so. The MMR and MMRV vaccines are safe and effective, and herd immunity is the way to put many diseases out of business.

Not being vaccinated, or not getting children vaccinated according to the proper schedule, endangers the lives of babies under one year of age—they can’t get the first dose of the MMR (measles-mumps-rubella) or MMRV (measles-mumps-rubella-varicella) vaccine until they’re at least 12 months old (or 6-11 months old in special cases). Check out the CDC’s measles vaccine page for more information about the dosage and timing of these vaccines.

Measles elimination is a huge public health achievement—the WHO reports that between 2000 and 2017, measles vaccination prevented an estimated 21.1 million deaths. In recent years, there have been outbreaks in the US, but the majority of children are still receiving their routine measles vaccines—for the 2018-19 school year, 94.7% of kindergarten students had received 2 doses of the MMR vaccine.

Want to learn more about the immune system and how it protects the body? Check out these resources from the VB Blog and Learn Site:

- (Learn Site) Reacting and Adapting to Disease: How the Immune System Protects the Body

- The Lymphatic System: Innate and Adaptive Immunity

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you an instructor? We have award-winning 3D products and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.

Additional Sources: