Posted on 7/27/19 by Laura Snider

When was the last time you talked about the human placenta, platelets, and the majestic platypus in one sentence (or even one conversation)? Unless you’ve already read this new study published in Biology Letters, the connection between those subjects probably isn’t too clear—but you’re in luck because today we’re going to check out what platypuses and platelets have to do with the human placenta!

First, the placenta. During pregnancy, the placenta is a structure attached to the wall of the uterus that allows for the exchange of nutrients, gases, and wastes between the fetal and maternal bloodstreams.

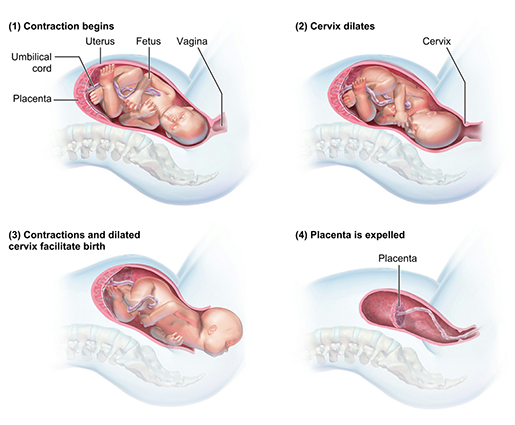

The type of placenta humans have is known as a hemochorial placenta because of the way the maternal and fetal bloodstreams interact. The fetus is connected to the placenta via the umbilical cord. Fetal blood flows through structures inside the placenta called chorionic villi, which are surrounded by maternal blood. Waste can diffuse across the chorionic villi from the fetal to the maternal bloodstream and nutrients can diffuse from the maternal to the fetal bloodstream. The placenta is typically ejected from the uterus a few minutes after a baby is born.

Image from A&P 6.

Image from A&P 6.

Now let’s talk about platelets. According to this study, the development of platelets made hemochorial placentation possible. Why? Platelets are cell fragments in the blood that help seal up wounds, keeping us from bleeding indefinitely (hooray!).

Platelets are hypothesized to have made hemochorial placentation possible because when the placenta detaches from the uterus after the baby is born, platelets help keep the mother from hemorrhaging.

Finally, we’ll bring in the platypus—well, more accurately, a common ancestor we share with the platypus. It was in this platypus-like creature that platelets first arose. Around 300 million years ago, the group this animal belonged to diverged into monotremes (like the echidna and platypus), marsupials, and eutherian mammals (the kind of mammals humans are). So, basically, we can thank this mysterious, weird-looking common ancestor for the fact that we have platelets to help our blood clot and, consequently, to make childbirth less deadly.

Fun fact: Non-mammalian vertebrates like birds and reptiles have nucleated thrombocytes instead of platelets to help their blood clot. Platelets are sometimes referred to as thrombocytes, but platelets in mammals don’t have nuclei.

Ultimately, there are two main take-home points from this study:

If you’d like to learn more about anatomy topics related to this article, check out these pages from the Visible Body Learn Site:

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you a professor (or know someone who is)? We have awesome visuals and resources for your anatomy and physiology course!

Additional Sources:

When you select "Subscribe" you will start receiving our email newsletter. Use the links at the bottom of any email to manage the type of emails you receive or to unsubscribe. See our privacy policy for additional details.

©2025 Visible Body, a division of Cengage Learning