The Deadly Dozen: The 12 Most Foreboding Chest Injuries Part I

Posted on 8/8/19 by Madison Oppenheim

"The Deadly Dozen," boy, does that sound ominous! Who knew that life-threatening thoracic trauma conditions could have such a sinister yet snazzy name. And get this, within The Deadly Dozen, we have "The Lethal Six" and "The Hidden Six." How fun! The catchiness of these names almost makes you not start to question your own mortality.

Now I know what you're thinking, "Hey, wasn't that a 1967 American war film directed by Robert Aldrich?" No, that would be The Dirty Dozen; close though!

The Deadly Dozen, which in my humble opinion, has a much more menacing name, refers to 12 life-threatening thoracic injuries. Six are imminent life threats (The Lethal Six) that should be evaluated and treated in the primary assessment, and six are potential life threats (The Hidden Six) that should be detected during the secondary assessment. For the sake of everyone's attention spans, this blog post is part one of two; here we will cover the basics of patient assessment as well as The Lethal Six.

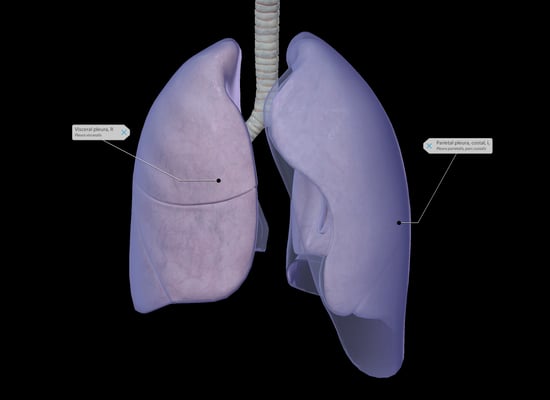

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas 2020.

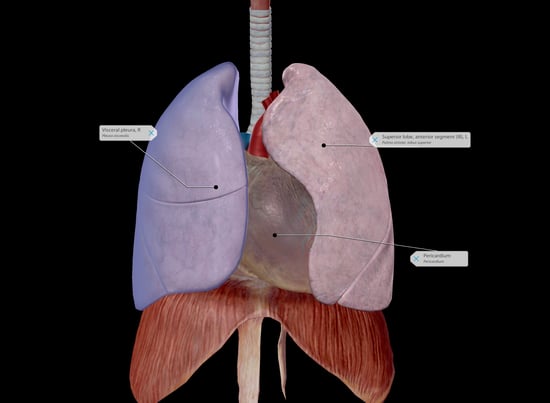

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas 2020.

Now if you remember my last blog post, I talked about being knee-deep in EMT school. Well, I finished my class, took my exams, and now I'm a certified EMT! Sorry to flex on you like that, I just wanted to mention that in school I learned that thoracic injuries account for approximately 25% of trauma-related deaths. Injuries to the great vessels or heart disruption usually result in immediate death. On the other hand, cardiac tamponade, tension pneumothorax, aspiration, or airway obstructions give you a little wiggle room (death within 30 minutes to three hours). Some of these thoracic injuries (namely the cardiac conditions) require emergent surgical intervention, but 85% of chest injuries can be treated by applying certain initial trauma management skills.

Patient Assessment

Alright, now earlier I mentioned the terms "primary assessment" and "secondary assessment." If you're not familiar with that terminology, I'll break it down.

When treating a patient, the first step after assessing the scene safety and applying appropriate personal protective equipment (gloves, mask, face shield, etc) is the primary assessment. This is where you get the chief complaint (the reason for calling 911) and determine if there are any life-threats requiring immediate intervention. In all trauma patients, the initial priorities are evaluation and management of the airway, breathing, and circulation; cervical spine stabilization; and determining the level of consciousness. Next, you would perform a more detailed secondary assessment, obtaining vital signs and assessing the area of injury. Depending on the patient's level of consciousness, a full-body assessment may be performed. If possible, a patient history would be taken, and during transport the EMT would perform a reassessment every 5 minutes for unstable patients, or 15 minutes for stable patients.

Okay enough playing around, time to get into the meat of this blog post: the injuries that can kill you.

The Lethal Six

"The Lethal Six." That sounds like the name of a top-grossing Mission Impossible-esque action film: a team of six spunky, disavowed assassins just trying to save the world from chaos. I'd watch it.

These six injuries are immediate life threats that need to be addressed during the primary.

1. Airway Obstruction

First off is the classic airway obstruction. The AOB—as it's referred to in the medical community—can either be a primary issue or the result of another injury. The most common cause of an AOB in an unconscious patient is the tongue, but dentures, teeth, secretions, and blood can all contribute in trauma cases.

Patients with AOBs need to be intubated early, while simultaneously protecting the C-spine, because airway edema (swelling caused by excess fluid trapped within tissues) can be progressive and treacherous.

2. Tension Pneumothorax

A pneumothorax is just a fancy way of saying collapsed lung. A tension pneumothorax occurs when a "one-way-valve" air leak occurs, where air escapes into the pleural space (the space between the visceral and parietal pleura: membranes that line the lungs and thoracic cavity respectfully) but can't return. This results in the affected lung completely collapsing. The mediastinum (the sac containing the heart, thymus, and parts of the esophagus and trachea) is then displaced to the opposite side, which decreases venous return and compresses the opposite lung, heart, great vessels, and trachea. Yikes.

Image showing the visceral and parietal pleura from Human Anatomy Atlas 2020.

Image showing the visceral and parietal pleura from Human Anatomy Atlas 2020.

The most common causes are penetrating chest trauma, mechanical positive pressure ventilation, accidental lung puncture from a medical procedure, or blunt chest trauma.

Treatment for a tension pneumo involves immediate decompression via insertion of a large-bore needle into the 2nd intercostal space along the midclavicular line of the affected hemithorax (half of the chest). Then a chest tube would be immediately inserted.

3. Cardiac Tamponade

Cardiac tamponade (also referred to as pericardial tamponade) is most commonly due to penetrating trauma. When as little as 50 mL of blood accumulates in the pericardial sac (which surrounds the heart), it puts pressure on the heart muscle, preventing it from being able to adequately refill with each contraction. Cardiac output, perfusion, and venous return decrease and the heart is unable to effectively fill and/or pump, leading to cardiac arrest. Beck's triad is the classic presentation: narrowing pulse pressure, jugular vein distention, and muffled heart sounds.

Image showing the right visceral pleura, left lung, and pericardium from Human Anatomy Atlas 2020.

Image showing the right visceral pleura, left lung, and pericardium from Human Anatomy Atlas 2020.

To treat cardiac tamponade, the heart needs to be surgically repaired. The blood and clots in the pericardium need to be drained. Aggressive airway protection, hemodynamic support, and fluid resuscitation are musts.

4. Open Pneumothorax

This bad boy is also known as a "sucking chest wound." This type of pneumothorax occurs when there's a giant open hole in the chest, usually due to penetrating injury or impalement. The pleural space is open to the atmosphere, causing equilibrium between intrathoracic pressure and atmospheric pressure, which to put it simply, is muy malo. Ventilation (the movement of air in and out of the lungs) occurs due to negative pressure. The diaphragm and intercostal muscles contract, causing the lungs to expand and fill with air. If there is no pressure gradient, you can't breathe. In an open pneumothorax, air accumulates into the hemithorax with every inspiration, leading to profound hypoventilation and hypoxia.

A three-sided occlusive dressing is used alongside direct pressure to treat. This dressing acts as a one-way valve to revive the pressure gradient. A chest tube would also be inserted if the patient was not intubated.

5. Massive Hemothorax

A hemothorax (not the same as the term hemithorax, which refers to one half of the thorax) occurs when blood collects in the pleural cavity. The addition of "massive" indicates a rapid accumulation of greater than 1,500 mL of blood. Yeah, that's a lot. The average adult has about 5-6 L (5,000-6,000 mL) coursing through their body at any one time.

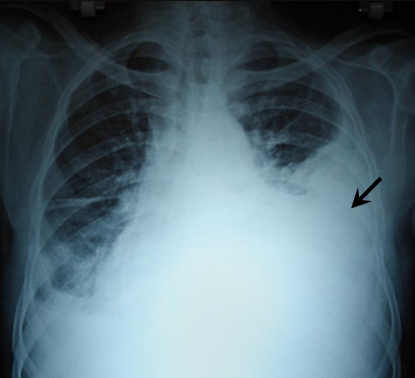

Unaltered image of a massive hemothorax from Salim S.

Unaltered image of a massive hemothorax from Salim S.

Hemothoraces are most often caused by a laceration to the lung, intercostal vessel, or internal mammary artery due to either blunt or penetrating trauma. In the case of a massive hemothorax, the cause is usually penetrating trauma with blood vessel disruption. A left-sided hemothorax is more common than a right-sided one and is typically the result of an aortic rupture.

To treat, the blood must be removed ASAP. If initial drainage of more than 1,500 mL of blood, or ongoing hemorrhage (bleeding) over more than 200 mL/hour over 3-4 hours occurs, an urgent thoracotomy (incision into the chest wall) is generally indicated. The patient would also be intubated due to the likely presence of shock and a chest tube would be inserted to prevent tamponade. There are numerous types of shock but in this case, hemorrhagic shock (rapid blood loss causing the body to shut down) is most likely.

6. Flail Chest

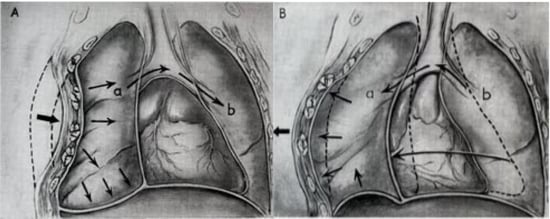

Last but not least, everybody's favorite: flail chest. It is defined as unstable segments of 2-3 or more ribs that are fractured in at least 2 different places moving separately from the rest of the chest. These free-floating segments result in paradoxical motion: all or part of the lung inflates during inspiration and balloons out during exhalation, the opposite of normal chest motion. They're following pleural pressure instead of respiratory muscle activity.

Reformatted image showing flail chest from the U.S. Army.

Reformatted image showing flail chest from the U.S. Army.

Treatment involves appropriate airway management, a bulky dressing, and ventilation with a bag-valve mask (BVM) to essentially splint the chest from the inside out. Providing positive-pressure ventilations (like with a BVM) with the pressure from the bulky dressing, allows the flail segment to be stabilized and normal breathing to be restored.

You made it! Make sure you're on our email list so you can receive an alert when part two drops; you won't want to miss The Hidden Six! You can sign up for our newsletter by scrolling down to the very bottom of the page.

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you an instructor? We have award-winning 3D products and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.

Additional Sources:

Cubasch H, Degiannis E. "The deadly dozen of chest trauma." J Contin Med Education 22 7 (2004): 369–372.

Yamamoto, Linda Masayo et al. “Thoracic trauma: the deadly dozen.” Critical Care Nursing Quarterly 28 1 (2005): 22-40.