The Amazing Appendix: An Anatomical Mystery

Posted on 7/18/19 by Laura Snider and Nick Riley

Does the appendix have a purpose? It may seem like a trivial question, right up there with “what should I have for dinner tonight?” but the answer is quite complex and can teach us a great deal about how our bodies work.

Facts About the Appendix

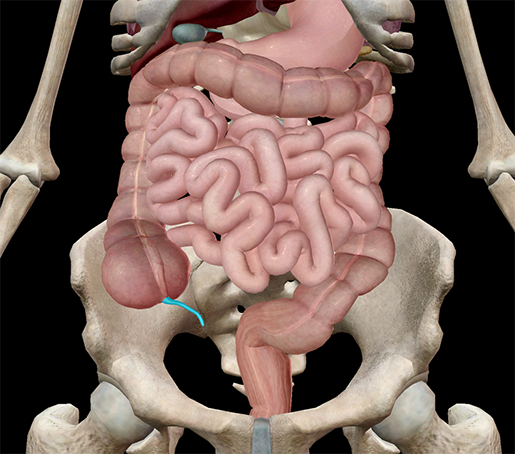

Before we get into all that, though, let’s talk about what we know for sure about the appendix. The appendix is located in the abdominal cavity, just off of the cecum, where material from the small intestine enters the large intestine. Being on the shorter side, the appendix only measures 8-10 cm long and is no wider than 1.3 cm. That’s about the same size as your pinky finger!

The appendix (highlighted) in context. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

The appendix (highlighted) in context. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

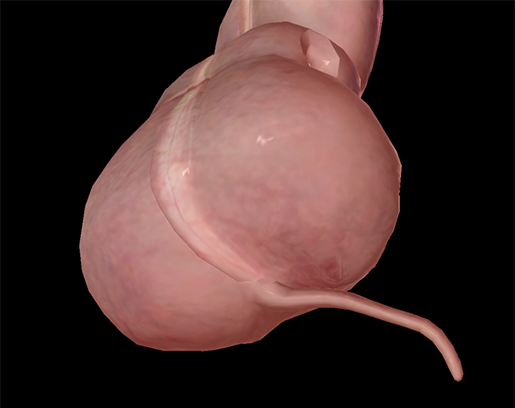

Interestingly, the appendix’s official name is the vermiform appendix (appendix vermiformis), which roughly translates to “worm-like appendage.” It kind of does look like a little worm!

Not So Useless After All

For many years, the appendix has been thought of as a useless body part, a vestigial structure that will eventually disappear as the human body evolves.

The main reason this body part was thought of as useless is that it was assumed the appendix used to be part of the digestive system. For example, Charles Darwin thought that in the ancestors of humans and great apes, it was actually part of the cecum and aided in the digestion of tough plant fibers. Darwin proposed that the part of the cecum that became the appendix shrank once apes began eating fruit, which was easier to digest.

The appendix, in all its worm-shaped glory, sticking out of the cecum.

The appendix, in all its worm-shaped glory, sticking out of the cecum.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Another reason people wrote off the appendix as useless is that people can live just fine without one. In cases of appendicitis, the appendix becomes inflamed and must often be removed, showing that it’s not essential for survival.

However, just because something isn’t essential doesn’t mean it isn’t useful. Recent research has shown that the appendix may serve a purpose and—contrary to Darwin’s proposal—it is not directly part of the digestive system. Instead, the appendix could play an important role in immune function.

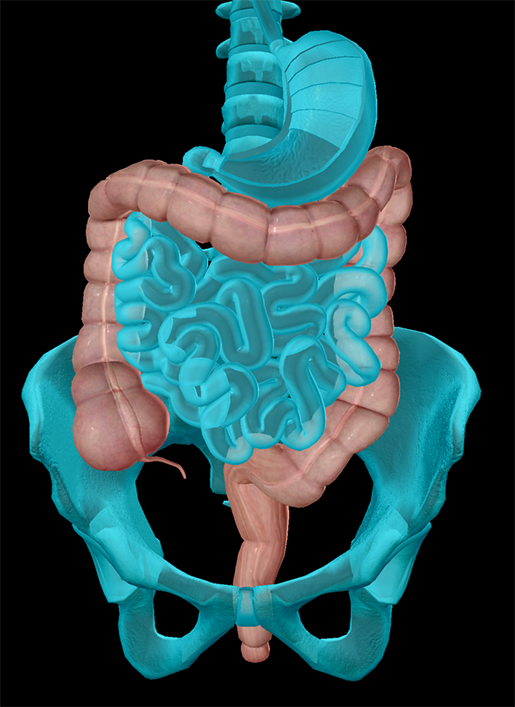

In their 2007 paper, William Parker and his colleagues at Duke University proposed that the appendix serves as a reservoir or “safe house” for gut bacteria. Gut bacteria (or gut flora) are “good” bacteria that line the large intestine and work alongside the immune system to fight off disease-causing microorganisms and substances. They also help the large intestine digest carbohydrates that were not fully digested in the small intestine.

The Duke scientists’ hypothesis goes like this. Certain diseases, like cholera or amoebic dysentery, wreak havoc on the beneficial bacteria living in the large intestine, thoroughly depleting their population. When someone is infected with one of these diseases, the appendix serves as a “safe haven” where the gut flora can weather the storm. Then, they can repopulate the large intestine once the illness has run its course.

The large intestine. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

The large intestine. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

A 2011 study published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology provides some interesting support for the idea of the appendix as a reservoir for gut bacteria. James Grendell and his colleagues looked at the recurrence rate of Clostridirum difficile (C. difficile, or “C. diff” for short) infection in patients with or without an appendix. A C. difficile infection is particularly nasty because it often recurs after treatment, meaning that “the native fauna of the gut and immune system cannot, together, prevent it from reinvading.”

Basically, if the reservoir hypothesis is right, C. difficile’s reinvasion should be more successful in patients who can’t benefit from the “reboot” the appendix provides. Lo and behold, the study showed that C. difficile recurred in 11% of patients who still had their appendix and a whopping 48% of patients who’d previously had their appendix removed.

Want to know something else cool? About 50 other mammals are considered to have an appendix. What’s more, a 2013 study tracking the evolution of the appendix showed that these mammals didn’t undergo significant shifts in diet concurrent with the appearance of the appendix. (Sorry, Darwin.) Most interestingly of all, a 2017 study by the same team found that “species who had an appendix tend to have higher concentrations of lymphoid tissue in their cecum.”

Overall, then, things are looking good for the reservoir hypothesis, but many studies still need to be done to confirm whether the appendix really is a safe house for bacteria.

It'll Have To Come Out...Or Will It?

About 7% of people in the U.S. experience an unpleasant condition called appendicitis at some point in their lives, usually between the ages of 10 and 30.

Appendicitis happens when there is an obstruction of (or in) the appendix, leading the bacteria inside the appendix to multiply. This causes the appendix to become inflamed, swollen and filled with pus.

A characteristic symptom of appendicitis is pain in the lower right abdomen, which can worsen when you cough, walk, or make sudden movements. Sudden pain at the navel that moves down to the lower right abdomen is also possible. Other symptoms can include loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea, flatulence, abdominal bloating, and fever.

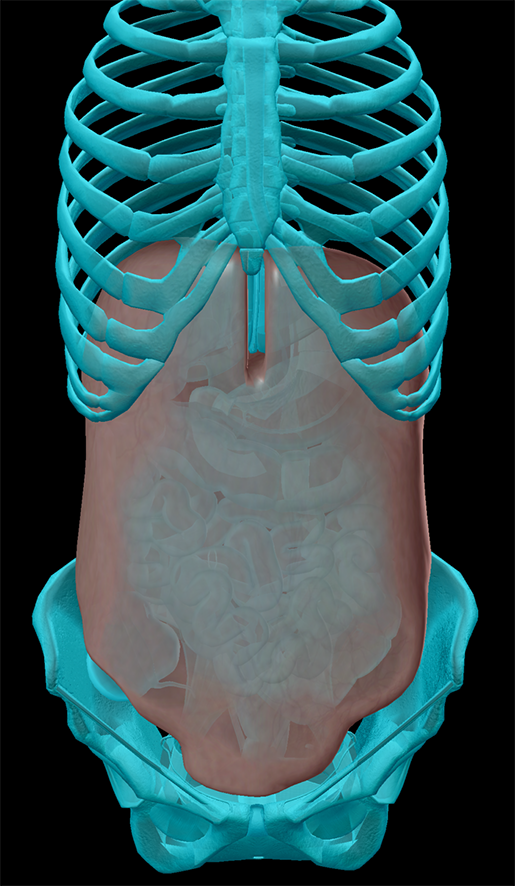

If not treated, the appendix gets more and more inflamed, eventually getting to a point when rupture is imminent. A ruptured appendix can lead to peritonitis, a potentially life-threatening infection of the tissue lining the abdominal cavity (the peritoneum).

The peritoneum. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

The peritoneum. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

It has been common practice that when a patient is diagnosed with appendicitis they will have surgery ASAP, removing the appendix from the body before it ruptures. If the appendix has already ruptured, immediate surgery is required to remove the remnants of the appendix and clean out the abdominal cavity.

There are two different types of appendectomy procedures: open and laparoscopic. Open appendectomy requires a 2–4 inch incision on the right side of the abdomen. Laparoscopic appendectomy involves 1 to 3 tiny incisions. Surgical tools and a long tube with a camera are inserted into the incisions and the surgeon guides their tools and keeps track of what they are doing using a TV monitor. Laparoscopic surgery is the option that requires less recovery time.

Similar to the typical thinking that the appendix is useless, the statement that a patient needs surgery as soon as they are diagnosed with appendicitis is being questioned. In 2015, a group of Finnish scientists showed that antibiotics can be used to treat some cases of uncomplicated acute appendicitis (when the appendix hasn’t ruptured and doesn’t have any perforations or abcesses). The benefits of antibiotic treatment are that it allows the appendix to remain in the body (after all, it may be beneficial to have!) and it avoids the risks inherent to surgery.

With the way research is going, it’s clear that the appendix isn’t just there to look pretty, so it looks like the short answer to the question of whether the appendix has a purpose is “probably.” We certainly don’t know everything about that purpose yet, but scientists are well on their way to figuring it out.

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you an instructor? We have award-winning 3D products and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.

Additional Sources: