Learning the ABCs: What Is Viral Hepatitis?

Posted on 10/9/20 by Laura Snider

This year’s Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine has been announced, and it’s being awarded to Harvey J. Alter, Michael Houghton, and Charles M. Rice for the discovery of hepatitis C virus. In the official press release, the Nobel Prize committee states that before Alter, Houghton, and Rice’s work, “the discovery of the Hepatitis A and B viruses had been critical steps forward, but the majority of blood-borne hepatitis cases remained unexplained. The discovery of Hepatitis C virus revealed the cause of the remaining cases of chronic hepatitis and made possible blood tests and new medicines that have saved millions of lives.”

In honor of these scientists’ accomplishments, we’re going to take a look at the different types of hepatitis and discuss what they have in common, how they differ from one another, and what sorts of vaccines and treatments are (or aren’t) available for each one. We’ll also talk about the specific contributions that Alter, Houghton, and Rice made to the study of hepatitis C.

What is hepatitis?

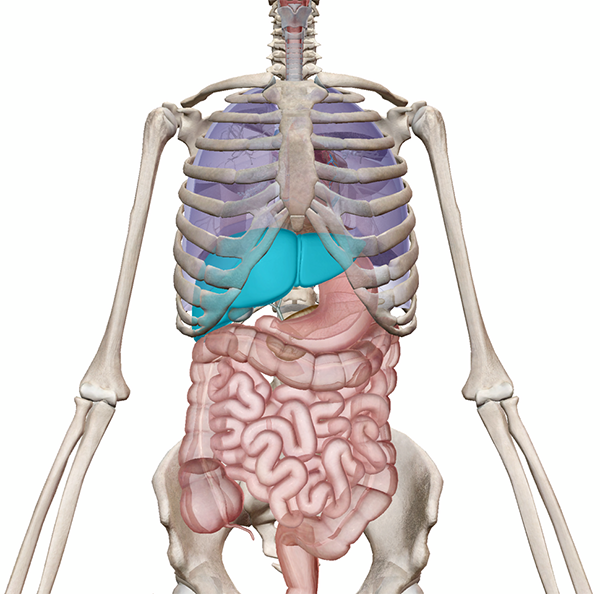

Hepatitis is a group of diseases that result in liver inflammation. The liver serves many important functions, including detoxifying the blood, producing blood proteins, producing bile to help the body digest fats, storing vitamins, and helping maintain glucose levels in the blood by producing and storing glycogen. Check out this VB blog post on the liver to learn more about the anatomy and function of the healthy liver!

Location of the liver relative to the heart, lungs, and digestive system. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Location of the liver relative to the heart, lungs, and digestive system. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Hepatitis is usually caused by one of several different viruses, but can also result from alcohol abuse, environmental toxins, or autoimmune disorders. Autoimmune hepatitis can often be treated with corticosteroids and/or immune-suppressing medications.

Some forms of hepatitis, such as hepatitis A and E, are acute. Others, like hepatitis B and C, are usually chronic. According to Healthline, acute hepatitis symptoms include:

- Fatigue

- Flu-like symptoms

- Dark urine

- Pale stool

- Abdominal pain

- Loss of appetite

- Unexplained weight loss

- Yellow skin and eyes (jaundice)

The symptoms of chronic hepatitis can be more difficult to notice because they occur more slowly over time.

A variety of diagnostic tests can be used to see if someone has a form of hepatitis, including liver function tests, hepatitis-specific blood tests, abdominal ultrasound (to check for fluid in the abdomen, liver damage, liver tumors, and gallbladder abnormalities), and liver biopsy. Liver biopsies for hepatitis diagnosis don’t usually require surgery, but they are still invasive. Often, a tissue sample of the liver will be collected using a needle through the skin.

Treatment is based on what type of hepatitis is present, which brings us to the next part of our discussion—the specifics of hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E.

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A is caused by the hepatitis A virus (HAV), which is present in the blood and stool of infected individuals and is usually transmitted through contaminated food or water. Typical symptoms include fatigue, nausea, stomach pain, and jaundice. Infection in the elderly or people with chronic liver disease can be more dangerous, possibly leading to liver failure.

Illness caused by HAV is short term, lasting from several weeks to several months, and doesn’t usually cause lasting liver damage. Treatment is primarily focused on addressing symptoms and providing adequate hydration, nutrition, and rest.

Fortunately, HAV infection is vaccine-preventable. The hepatitis A vaccine is part of the normal immunization schedule for children in the US. It’s administered in a series of two injections at a minimum of six months apart, starting when the child is about a year old.

Hepatitis B

The hepatitis B virus (HBV) was identified by Baruch Blumberg in the 1960s. Diagnostic blood tests and a vaccine were developed based on his discovery (which earned him the 1976 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine). Like the vaccine for hepatitis A, the hepatitis B vaccine is a routine part of the immunization schedule for children in the US. The first dose is usually administered within 24 hours of birth.

HBV infection is transmitted via blood, semen, or other bodily fluids. Sexual contact or sharing needles with an infected individual can transmit the virus. A mother who has HBV can also pass it to her baby at birth.

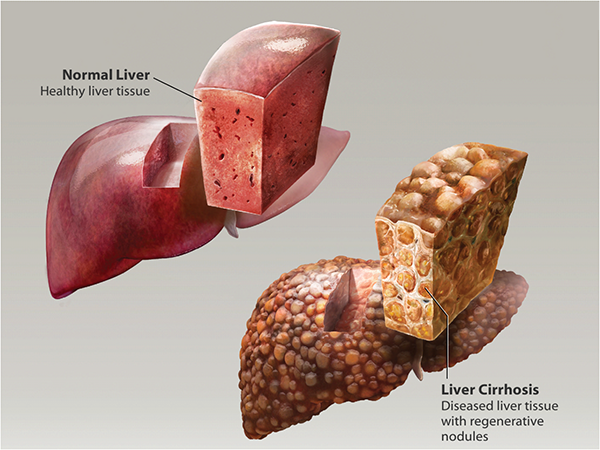

Hepatitis B can be either short-term or long-term. If HBV infection persists at a chronic level, it can lead to liver cancer or cirrhosis (extensive scarring) of the liver.

A comparison of healthy and cirrhotic liver tissue. Illustration from Physiology & Pathology.

A comparison of healthy and cirrhotic liver tissue. Illustration from Physiology & Pathology.

There isn’t a specific treatment for acute hepatitis B, but chronic hepatitis B is typically treated with antiviral medications.

Hepatitis C

Like hepatitis B, hepatitis C is transmitted via contact with blood or bodily fluids from an infected individual. It can also be acute or chronic, with chronic infection leading to complications like cirrhosis and liver cancer.

The hepatitis C virus was not identified until well after HAV and HBV. In the 1970s, Harvey J. Alter studied patients contracting hepatitis following blood transfusions (but this form of hepatitis was neither A or B when they were tested). Michael Houghton isolated and identified the new virus, and Charles M. Rice confirmed that it was indeed the new hepatitis C virus that was causing disease.

All told, these discoveries led to blood tests that have drastically reduced the number of people who contract hepatitis C via blood transfusions, and antiviral drugs to treat chronic hepatitis C infections.

Hepatitis D and E

Though hepatitis A, B, and C are the most common types of viral hepatitis, there are two others (hepatitis D and E).

Hepatitis D is rare in that it will only occur in people who have been infected with hepatitis B. Hepatitis D infection can occur either at the same time as hepatitis B infection or after hepatitis B infection. Although there is no vaccine for the virus that causes hepatitis D, vaccination that protects against hepatitis B will also prevent hepatitis D infection.

Similar to hepatitis A, hepatitis E can be found in the stool of infected individuals, and others can contract the disease when they consume contaminated food or water. Hepatitis E is rare in the US and is more often seen in developing countries, where drinking water might be contaminated. According to the CDC, “travelers to developing countries can reduce their risk for infection by not drinking unpurified water. Boiling and chlorination of water will inactivate HEV.” There is no specific treatment or vaccine for hepatitis E.

The Big Picture

Overall, around 71 million people worldwide have chronic hepatitis C, and the WHO reports that around 400,000 people die from hepatitis C every year. The research contributions made by Alter, Houghton, and Rice have been a key part of preventing and fighting this deadly disease.

The main obstacle to eliminating hepatitis C is the cost of treatment. Widely accessible diagnostic tests and antiviral treatments will be key to getting rid of hepatitis C for good. Currently, there isn’t a hepatitis C vaccine available—hepatitis C has a large number of subtypes, and a global vaccine would have to protect against all of them. However, research is ongoing, and there may yet be a hepatitis C vaccine in the world’s future.

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you an instructor? We have award-winning 3D products and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.