How Abnormal Reflexes Can Indicate Pathologies

Posted on 8/25/23 by Sarah Boudreau

Simply speaking, reflexes are muscle movements that happen without us telling the body what to do. A reflex is an automatic response to stimulus, beginning before impulses reach the brain.

The first thing that might come to mind is the classic knee jerk reflex, where the doctor uses the reflex hammer to gently tap your knee, and in response, your leg kicks out. If your leg doesn’t kick, it’s an indication that somewhere along the line, the nerves are not passing messages along the right way. By testing reflexes, doctors can quickly check up on the nervous system.

Did you know that the presence of some reflexes in adults can point towards nervous system damage? Today on the Visible Body Blog, we’re walking you through some examples of abnormal reflexes in adults!

Babinski reflex

The Babinski reflex is when the bottom of the foot is stroked and the big toe moves upwards. The other toes may also fan out. It’s a normal reflex in infants and young children, and it typically disappears around age two.

It was first described by Joseph Babinski in 1896, and it’s still commonly used as a diagnostic tool. To look for this reflex, a doctor uses a dull instrument (like the point of a reflex hammer) and runs it up the lateral plantar side of the foot and across the metatarsal pads to the base of the big toe.

Image from Visible Body Suite.

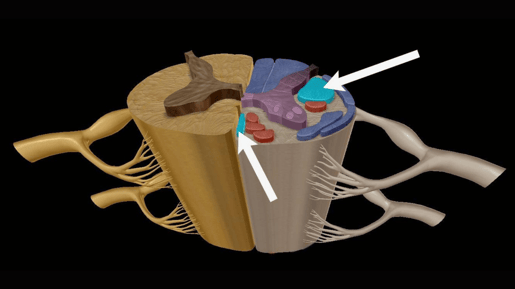

When the reflex is present in adults, it is called a Babinski sign. A Babinski sign indicates damage somewhere along the corticospinal tract (CST), a major pathway that provides voluntary motor function. When the CST is damaged, sensory input spreads beyond the associated nerve cells. This leads to other motor neurons firing, which causes the big toe to extend when the bottom of the foot is stroked.

The anterior CST (left) and lateral CST (right). Spinal cord cross section from Visible Body Suite.

In an adult without CST damage, when the bottom of the foot is stimulated, the toes curl down. In some cases, there is no response (a neutral response), but that doesn’t rule out pathology.

Frontal release signs

Next, let’s discuss a group called frontal release signs. Frontal release signs are the presence of reflexes like the glabellar, suck, snout, and palmomental reflexes in adults—in infants, they're perfectly normal.

- The glabellar reflex: when the forehead is tapped repetitively, the patient continues to blink uncontrollably.

- The snout reflex: the lips pucker into a snout shape when pressure is applied to the upper lip.

- The suck reflex: the lips make a sucking movement when touched.

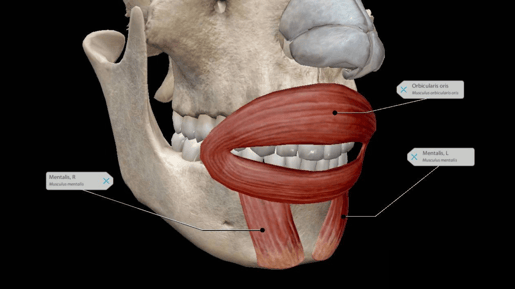

- The palmomental reflex: when the palm is stroked, the orbicularis oris and mentalis muscles contract.

The orbicularis oris and mentalis muscles. Image from Visible Body Suite.

These reflexes fall under the category of primitive reflexes, which are reflexes that young babies have in order to survive. As the brain matures, primitive reflexes are replaced by voluntary motor activities. By four to six months of age, babies typically develop control over their own bodies and are able to move without relying on reflexes, and primitive reflexes disappear.

The presence of frontal release signs point towards frontal lobe diseases like dementia and closed head trauma, though it’s worth mentioning that many healthy people have frontal release signs and many people with frontal lobe diseases do not.

The grasp reflex

Another primitive reflex associated with frontal lobe damage is the grasp reflex. This reflex is elicited by deep pressure over the palm of the hand.

The grasp reflex happens in two phases: catching and holding. In the catching phase, the muscles contract, and in the holding phase, the tendons maintain traction. The grasp reflex typically goes away by four to six months of age, and the reemergence of the grasp reflex in adulthood can make daily life more difficult and decrease independence because it makes it harder for the patient to use their hands.

Researchers haven’t yet mapped out the neural circuit associated with the grasp reflex, but we do know that several pathologies are connected to a reemergence of the reflex, like Parkinson's disease and dementia. It’s estimated that the grasp reflex is present in about 0.1% of healthy adults over the age of 65—but it’s present in about 18.4% of adults over 65 with dementia.

The left and right frontal lobes. Image from Visible Body Suite.

Clonus

Unlike the other reflexes we’ve talked about so far, clonus can occur in many different muscles, though it most often affects the muscles in the ankles and knees.

Clonus is the presence of muscle movements that are rhythmic and involuntary. Researchers aren’t yet sure of the pathophysiology behind clonus, but the reflex is connected to damaged nerve pathways. Clonus appears in conditions such as

- Cerebral palsy

- Stroke

- Multiple sclerosis

- Spinal cord injury

- Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (also known as ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease)

It’s easy to test for clonus. Testing is usually done with the ankle. The patient lies down in a relaxed position with a passively flexed ankle and passively flexed knee. The examiner will then rapidly dorsiflex the ankle and maintain pressure. If clonus is present, the examiner will feel rhythmic beats as the ankle cycles through plantarflexion, relaxation, and plantarflexion.

Dorsiflexion GIF from from Visible Body Suite.

Conclusion

In this blog post, we’ve talked about several different reflexes:

- The Babinski reflex, which is a sign of CST damage

- Frontal release signs, which point towards frontal lobe damage

- The grasp reflex, which also is a sign of frontal lobe damage

- Clonus, which is connected to damaged nerve pathways

If you’re interested in learning more about pathologies that affect the nervous system, check out these blog posts!

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you an instructor? We have award-winning 3D products and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.