Flu Vaccines Are Nothing to Sneeze At

Posted on 11/25/22 by Sarah Boudreau

It’s the most wonderful time of the year: time to get your flu vaccine! Let’s explore the Spanish flu epidemic, the development of the flu vaccine, and what the flu vaccine is like today.

The Spanish flu pandemic

The Spanish flu, one of the deadliest pandemics in human history, shows us how dark the world was without flu vaccines.

The flu was a serious illness, cycling seasonally and tending to hit the elderly the hardest. However, it wasn’t as deadly as diseases like smallpox, which was already on its way to being defeated by vaccines.

The Spanish flu thrived during the tail end of World War I. The trench warfare of the Western Front was a breeding ground for disease: between intermittent bouts of terrifying combat, troops were crammed together in the unsanitary, wet conditions.

Troops dealt with lice and disease-spreading rats, and they suffered from diseases that thrived in the close quarters and mud of the trenches.

Enter the Spanish flu. Contrary to popular belief, the Spanish flu did not originate in Spain. The flu likely affected neutral countries and Allied and Central Powers alike, but the warring countries were hesitant to report any weakness, and because Spain was a neutral country in World War I, it had nothing to lose by honestly reporting the spread of the illness.

The Spanish flu began with head soreness, fatigue, and a dry cough followed by stomach problems and respiratory distress. Normal flu symptoms soon turned into severe pneumonia, and the disease mostly affected people in their late teens and early twenties.

By summer 1918, the flu had spread across mainland Europe and traveled with soldiers returning to North America. Soon it spread across the globe. All in all, it infected over 500 million people.

Tent city created to quarantine influenza patients in Lawrence, Massachusetts. Photo from the National Archives.

Tent city created to quarantine influenza patients in Lawrence, Massachusetts. Photo from the National Archives.

Doctors could do little to mitigate the Spanish flu, and many people turned to ineffective and sometimes dangerous cures like taking laxatives, consuming six times the safe dosage of aspirin, and bloodletting. Some British parents even made their sick children inhale chlorine gas to try to reduce their symptoms.

With no vaccine, the Spanish flu killed between 20 and 50 million people—more people than the entirety of World War I, and approximately 1-3% of the total world population.

Development of the vaccine

It was clear to the world that they needed a better way to prevent a flu pandemic from happening again. However, vaccine development was in its infancy. Vaccines had never been rolled out in large numbers, and they had only been used with a handful of diseases like smallpox and tetanus.

Scientists need a thorough understanding of a microbe in order to develop a vaccine for it, and the flu proved hard to pin down. Fifteen years after the Spanish flu, British researchers at the National Institute for Medical Research discovered that the flu was a virus, not a bacteria as previously thought. They were able to isolate the virus, but many challenges lay ahead.

With World War II in full swing, the United States military feared that a flu epidemic like the Spanish flu would decimate their troops again, so the US invested in developing a vaccine.

The American physician and virologist Thomas Francis discovered that the influenza virus changes its chemical structure, which means that the body’s immune system can’t recognize new strains.

Let’s back up for a second. We now know that there are four types of flu virus: A, B, C, and D. A and B are responsible for the seasonal flu viruses that hit every winter, while a C virus is mild and does not cause epidemics. D doesn’t cause illness in people. Influenza A viruses can be divided into subtypes based on the proteins hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). With 18 different hemagglutinin types and 11 different neuraminidase types, there are over 130 influenza A combinations. The subtypes can be broken down further into different “clades” and even “sub-clades.” It gets even more complicated: two genetically identical viruses can be antigenically different, which means they’re recognized differently by the immune system.

Now put yourself in the shoes of a scientist from the late 1930s, when it was only recently discovered that the flu wasn’t caused by bacteria. At the time, the flu was a virus you couldn’t test for or even see, as electron microscopes had not yet been invented. The challenge seems insurmountable.

Francis and up-and-coming virologist Jonas Salk (who would go on to develop the polio vaccine) developed an inactivated flu vaccine. Salk used chicken eggs to incubate the flu virus. He would then extract the virus and use chemicals like diluted formaldehyde to “kill” the virus, making it harmless while still triggering the body’s immune response. This vaccine was designed to protect against influenza B and the H1N1 strain of influenza A.

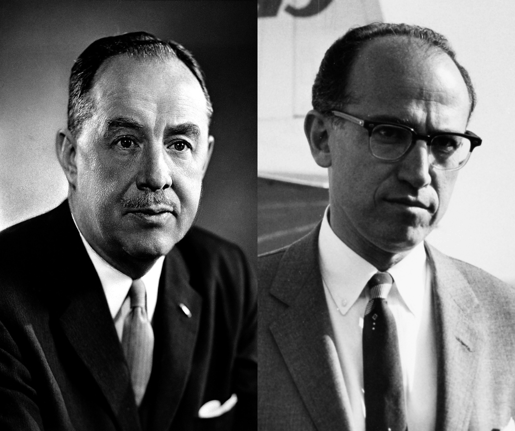

Thomas Francis Jr. (left) and Jonas Salk (right). Photos from Wikipedia Commons.

Thomas Francis Jr. (left) and Jonas Salk (right). Photos from Wikipedia Commons.

Medical research at the time was rife with human rights abuses as researchers would perform experiments on people with the least power, like the poor, the imprisoned, and minorities, often infecting them to study the effects of deadly diseases. In 1942, the early flu vaccine was tested on 8,000 institutionalized people at two psychiatric facilities in Michigan. None of those enrolled in the study consented. There was no flu outbreak that winter that could truly test the vaccine, so the next year, researchers selected 200 patients to infect with the flu. They found that in the group who received the placebo, half of the unwilling participants developed the flu, but in the group who received the vaccine, only 16% developed the flu.

The next step was a major trial, testing 12,500 participants of the Army Specialized Training Program with vaccines manufactured by major drug producers for two different flu strains. A mere 2% of vaccinated people caught the flu. The surgeon general ordered all members of the US Army to get inoculated in 1945, and when a Type B influenza hit that fall, it only hit 8% of the soldiers.

In 1947, researchers discovered that the two vaccines developed by Francis and Salk were not as effective as before. In response, the World Health Organization (WHO) established the Worldwide Influenza Center and the Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System to study how to produce more effective vaccines.

The flu vaccine today

Every year, WHO designs the vaccine that can best defeat the strains most likely to show up over the next flu season. Each vaccine contains two A strains and one B strain.

To decide this, WHO looks at data from influenza surveillance centers around the world. For the northern hemisphere, strains are chosen around February to allow enough time for production and thorough testing before people receive the vaccine. Notably, the “swine flu” epidemic of 2009 sprung up after the WHO had made their selections, so a separate vaccine had to be created.

.jpg?width=515&height=606&name=H1N1_influenza_virus%20(1).jpg) The H1N1 strain that led to the 2009-2010 flu epidemic. Image from the Centers of Disease Control.

The H1N1 strain that led to the 2009-2010 flu epidemic. Image from the Centers of Disease Control.

Thanks to WHO’s strain matching, the yearly flu vaccine reduces the risk of flu by 40-60%!

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has led to some interesting blips in flu data. In the 2019-2020 flu season, approximately 22,000 people in the United States died from the flu, but the very next season, the flu caused about 700 deaths. Why? The flu is transmitted in similar ways as the virus that causes COVID, so public health measures like masking and social distancing were very effective at stopping the spread of the flu. The numbers were so low that the Centers for Disease Control had to skip out on calculating the 2020-2021 flu shot effectiveness because they didn’t have enough data.

.jpg?width=515&height=386&name=My%20project%20(34).jpg) The flu vaccine is typically injected into the deltoid muscle of the upper arm. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

The flu vaccine is typically injected into the deltoid muscle of the upper arm. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

The 2021-2022 season saw an increase in cases, but that season still had lower numbers than before pandemic restrictions and the prevalence of COVID vaccines. Flu seasons tend to be unpredictable, so it’s unclear if the less intense season had any one cause. Some researchers worry that herd immunity to the flu has decreased due to two years of unusually mild numbers, but they all agree that the flu vaccine is the most important step an individual can take to prevent the flu.

We can try to keep up our global streak of mild flu seasons by getting flu shots this year!

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more awesomeness!

Are you an instructor? We have award-winning 3D products and resources for your anatomy and physiology or biology course! Learn more here.