Darwin's Finches Keep Evolving

Posted on 1/27/23 by Sarah Boudreau

In 1835, a young Charles Darwin arrived in the Galapagos Islands as part of the voyage of the HMS Beagle. The Beagle’s mission was to take measurements and chart the waters south of South America, but Darwin’s goal as the ship’s naturalist was to observe and take samples of the plants and animals he saw.

While in the Galapagos, Darwin collected specimens of several small, brown finches that had beaks of different shapes and sizes. Decades later, Darwin wrote On the Origin of Species, the book that established evolutionary theory, and now, the Galapagos finches are used as examples of natural selection in classrooms around the world. From one species that landed in the Galapagos one to two million years ago, those finches diversified into eighteen different species.

But what are the finches up to now?

They’ve kept busy, and they’ve kept evolving.

How species evolve

Let’s take a step back and talk about how the different finch species in the Galapagos Islands evolved in the first place. Evolution is the process by which populations change over time, and it happens through a mechanism called natural selection.

Natural selection means that when competing for resources and avoiding predators, organisms will survive and reproduce if they have traits that give them an advantage.

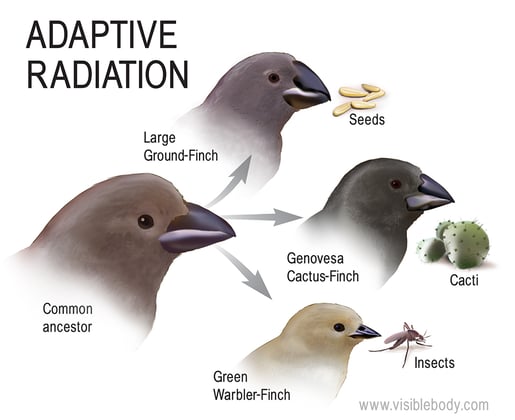

Considering the variations in beak size and use among the finches of the Galapagos, Darwin posited that these species all descended from one original species. As the finches competed for resources over generations, the population changed: as finches with traits that allowed them to survive and reproduce passed those traits down to their offspring.

Like us, finches need food to survive, and there are several different food sources on the islands. Over time, the finch population developed different traits that helped them take advantage of these resources—for example, some finches developed beaks that are great at picking up big seeds and some finches developed long, thin beaks that can eat food from cactuses without getting poked.

Eventually, the original finch population split up into different species. A species is defined as a population that can interbreed and create fertile offspring—medium ground finches reproduce with medium ground finches and cactus finches reproduce with cactus finches.

There are actually many different modes of selection and types of speciation (the process of becoming a new species)! For a more in-depth breakdown, check out the evolution section on Visible Body’s Learn Site, a free learning resource that walks you through basic biological concepts.

Learn about adaptive variation and more types of speciation on the Learn Site page for speciation!

Modern-day Darwins: Peter and Rosemary Grant

The formation of a new species can take a very, very long time—it depends on the type of organism. Some species take millions of years to develop, but in the Galapagos, a team of scientists have observed evolution in action.

Peter and Rosemary Grant, professors emeritus at Princeton University, are married biologists who have become legendary in their field. From 1973 to 2012, the Grants spent about six months of the year studying the finches of Daphne Major, a volcanic island in the center of the Galapagos.

Peter and Rosemary Grant. Photos by David Craig and accessed through Wikipedia Commons.

The Grants arrived in the Galapagos 114 years after Darwin’s visit, and they had a couple more tools at their disposal. For one, they had more time—Darwin only spent about five weeks in the islands, which is nowhere near enough time to observe a population changing. The Grants could also measure natural selection through statistics, and they brought with them a modern understanding of genetics. For example, collaborating with other researchers, they found several genes that affect beak shape.

Together, the Grants tagged about 20,000 birds, spanning eight generations, and were able to assemble pedigrees for the different finch species. Thanks to their hard work, we have exciting insight into how the finches of Daphne Major have changed over the years.

Droughts lead to changes in finch populations

The Grants spent half of the year on Daphne Major, but it’s hardly the ideal location for a summer home. Daphne Major is a weathered-down, dormant tuff cone volcano with steep sides and zero trees. It’s a tiny island, which means that it’s easier to keep track of the plants and animals that live there—in fact, during their tenure, the Grants banded almost every finch on the island.

To preserve its delicate ecosystem, Daphne Major is only accessible to researchers. Photo via Wikipedia Commons.

In 1977, four years after the Grants began their long-term research project, a major drought affected Daphne Major. The lack of water hit the island hard, and the plants produced far fewer seeds than normal. This was a huge problem for the medium ground finch, which relies on these seeds for food. The population dropped. There had once been about 1400 medium ground finches on the island, but two years after the drought hit, there were only a few hundred.

The Grants observed that after the drought, the average beak size went up by 4%. Why? During the drought, small seeds were rare, but larger seeds weren’t. The birds with smaller beaks couldn’t crack open the larger seeds to get to the food inside, but the birds with larger beaks could. The drought meant that the resources on the island shifted, and in turn, the medium ground finch population changed, too.

In 1982, it rained heavily, and Daphne Major suddenly had a large number of small seeds. The average beak size of the medium ground finch decreased by 2.5%—birds with smaller beaks could eat small seeds more efficiently than birds with larger beaks eating larger seeds.

.jpg?width=515&height=463&name=Female_Gal%C3%A1pagos_medium_ground_finch%20(1).jpg)

Female medium ground finch. Photo via Wikipedia Commons.

That year also marked the arrival of a Galapagos species new to Daphne Major: the large ground finch. The population of large ground finches grew over the next decades, which also affected the medium ground finch population. In 2004, another drought hit Daphne Major, killing off many medium and large ground finches.

But this time, the medium ground finch’s beak got smaller, even though small seeds were rare again. This is because the large ground finches muscled the medium ground finches out of the large seeds. The medium ground finches just couldn’t compete with their large ground finch cousins for large seeds, so the medium ground finches with smaller beaks were the ones who survived.

Finch hybridization

Remember how we said that different species don’t interbreed and create fertile offspring? Well, it’s actually a little more complicated than that. Some closely-related species like the Galapagos finches can interbreed with each other—but they typically do not. One reason is birdsong. Birds attract mates through song; for example, a cactus finch’s song will almost always attract exclusively cactus finches.

Hybridization is more commonly found in plants than in animals. Consider triticale, a hybrid of wheat and rye. Triticale is a human-made grain species that’s primarily used for animal feed. It holds up well in cold climates (like rye) and can be made into bread (like wheat).

It’s possible that hybridization in the wild can lead to new animal species if the hybrid offspring survive and pass on their genes. Hybrids tend to mate with their parent populations, which means that the offspring typically gets reabsorbed into the original species and no new species is created.

On Daphne Major, finch hybridization is thanks to Big Bird. No, not the Sesame Street character. “Big Bird” is the apt name the Grants and their team gave to a cactus finch from Española Island that flew over to Daphne Major in 1981.

Big Bird managed to breed with a medium ground finch, creating a new lineage that has continued through inbreeding for decades. The finches from the Big Bird lineage have unusual songs that do not attract mates from the three native species on Daphne Major, so they end up breeding with each other instead.

The Grants have been hesitant to declare the Big Bird lineage its own species because it’s not yet clear if the lineage will survive. It’s likely that the Galapagos finch species have interbred often over the years, but the case of Big Bird is still an interesting one because we witnessed hybridization happen after only two generations.

Big Bird’s lineage has the potential to officially create a new species—we’ll just have to wait and see.

Conclusion

The finches of the Galapagos Islands show us that the process of evolution is alive and well—and observable. As measured by Peter and Rosemary Grant, the medium ground finches of the island Daphne Major have adapted to their changing environment over time, experiencing drought, food abundance, and competition from other species. The Grants also observed hybridization that may lead to the creation of a new species.

Want to learn more? Check out these other blog posts!

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more awesomeness!

Are you an instructor? We have award-winning 3D products and resources for your anatomy and physiology or biology course! Learn more here.