Anatomy & Physiology: 4 Facts About the Cervix

Posted on 1/16/20 by Laura Snider

It’s January! Time for New Year’s resolutions and a whole lot of snow (for us New Englanders at least). But did you know that January is also Cervical Health Awareness Month? Now you do.

What’s so important about the cervix, you ask? The cervix is a vital part of the female reproductive system, playing a key role in conception and childbirth. But why is there a whole month dedicated to cervical health awareness? It turns out that a collection of viruses (forms of human papillomavirus) can lead to cancer in the tissue of the cervix. However, cervical cancer is highly preventable and treatable if caught early, so awareness is key to prevention!

We’ll discuss all that and more as we go through four key facts about the cervix.

1. The cervix connects the uterus and vagina

If you’re a word-nerd like me and you’ve wondered about the etymological link between the cervix and the cervical spine (the vertebrae that make up the neck), wonder no more. The official Latin name for the cervix is cervix uteri, which means “neck of the uterus.”

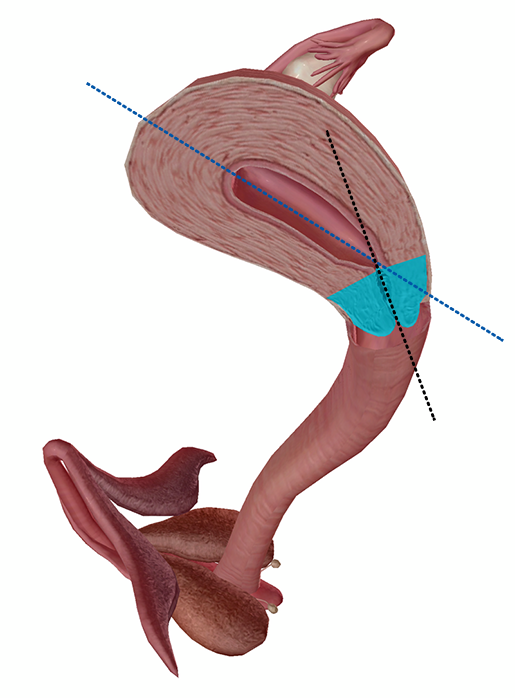

This parallel makes sense if we look at the shape and size of the cervix when compared with the rest of the uterus. It’s narrower than the body of the uterus, and the uterus bends on it—you can see in the image below how the long axis of the uterus and the cervix don’t quite line up.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

The cervix is (usually) about 4cm long in total, with a portion called the ectocervix that extends into the vaginal canal. The cervical canal is the tube-like center of the cervix, which connects the inside of the uterine cavity with the lumen of the vagina.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

The cervix serves as the passageway for anything that travels in or out of the uterus by way of the vagina—namely, sperm making their way in and menstrual blood and babies passing through into the outside world.

2. The cervix produces mucus

The mucous membrane lining the cervix contains glands that produce a clear, viscous, alkaline mucus. The consistency of this mucus changes throughout the menstrual cycle as well as when a person with a uterus becomes pregnant.

Mucus production ramps up just before the release of an egg (ovulation). During ovulation, cervical mucus facilitates fertilization by helping sperm travel from the vagina to the uterus. Its stretchy, egg-white-like texture, as well as its pH, are protective to sperm. When ovulation isn’t going on, the cervical mucus is generally thicker, serving as more of a barrier than an aid to sperm entering the uterus.

During pregnancy, mucus in the cervix forms a plug to protect the growing baby from bacteria and other sources of infection. The mucus plug usually passes out of the vagina shortly before labor begins. This is because the cervix must soften and dilate in preparation for childbirth, which means that it can’t hold the mucus plug in place as easily.

3. The cervix dilates during childbirth

When a baby is born, it must pass from the uterus, where it’s been growing for the past 37 weeks or so, into the vagina. In order for this to happen, the cervix needs to soften (efface) and open (dilate) to allow for the passage of the baby’s head.

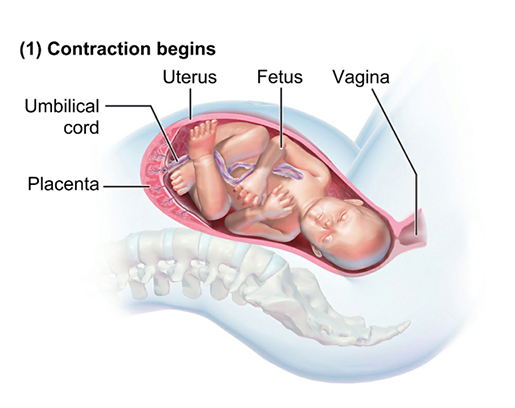

Labor has three(-ish) main stages. I say three-ish because Stage 1 (the dilation stage), in which the cervix plays a central role, has a latent phase and an active phase. During the latent phase, smooth muscles in the uterus begin to contract. The contractions start off irregular—they happen every 5-30 minutes and last about 30 seconds each.

The latent phase of Stage 1 of labor. Image from Anatomy & Physiology.

The latent phase of Stage 1 of labor. Image from Anatomy & Physiology.

As labor progresses, the contractions become more intense and closer together. Uterine contractions are stimulated by the release of oxytocin from the hypothalamus of both the mother and the baby. The placenta also secretes substances called prostaglandins, which stimulate uterine contractions in addition to facilitating the effacing and dilation of the cervix. Eventually, a positive feedback loop forms, in which uterine contractions cause the baby to push on and stretch the cervix. The stretching of the cervix stimulates the secretion of more oxytocin, which in turn stimulates more muscle contractions and the release of more prostaglandins.

During the latent phase, the cervix effaces about 30% and dilates to around 3cm. Then, regular contractions begin. These happen every 3-5 minutes and last about 1 minute each. The cervix continues to efface (to around 80%) and dilates to about 6cm.

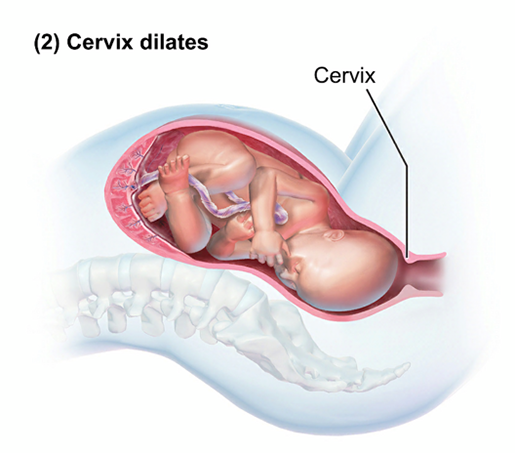

At this point, the active phase of Stage 1 begins. During the active stage, the cervix will become 100% effaced and will dilate to around 10cm. Contractions intensify, occurring every 30-120 seconds and lasting 60-90 seconds each. Active labor typically lasts from 4-8 hours, with the cervix dilating at a rate of 1cm an hour.

The active phase of Stage 1 of labor. Image from Anatomy & Physiology.

The active phase of Stage 1 of labor. Image from Anatomy & Physiology.

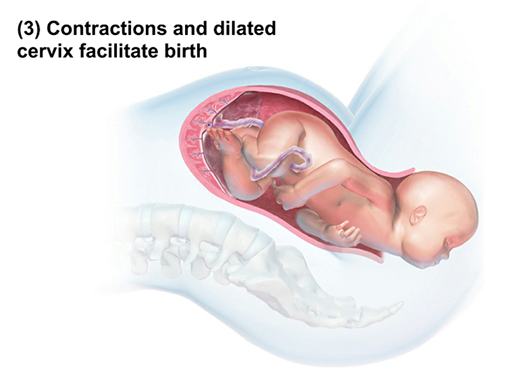

Once the cervix is fully effaced and has dilated to 10cm, Stage 2 of labor (the expulsion stage, or “pushing stage”) can begin. During this stage, uterine contractions and “bearing down” by the mother move the baby through, and then out of, the vagina. Stage 2 ends with the delivery of the baby.

Stage 2: The baby is born! Image from Anatomy & Physiology.

Stage 2: The baby is born! Image from Anatomy & Physiology.

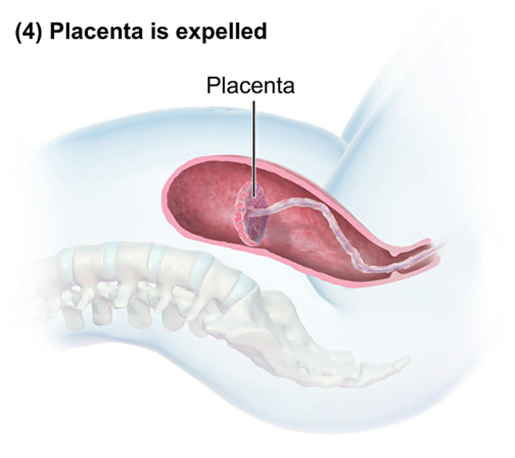

But wait! There’s more! After the delivery of the baby comes Stage 3, the placental stage, in which the placenta is expelled from the mother’s body.

Stage 3: delivery of the placenta. Image from Anatomy & Physiology.

Stage 3: delivery of the placenta. Image from Anatomy & Physiology.

4. HPV can lead to cervical cancer (and other cancers, too)

HPV (human papillomavirus) refers to a group of viruses which are spread via sexual contact. There are more than 200 of them, and they’re typically classified as being either high-risk or low-risk. The low-risk ones are the majority. While some may not cause disease at all, others can cause genital warts or warts around the anus, mouth, or throat.

It’s the approximately 14 high-risk HPVs that cause more serious problems, such as cervical cancer. HPV16 and HPV18 are the culprits when it comes to most HPV-related cancers.

HPV isn’t just responsible for cervical cancers: it can lead to a wide range of other cancers as well. Three percent of all cancers in women and two percent of all cancers in men are caused by HPV. All in all, HPV is responsible for:

- 75% percent of cancers of the vagina

- 70% of cancers of the vulva

- 60% of penile cancers

- 90% of anal cancers

Now, you might be wondering how a virus can lead to cancer. Let’s use cervical cancer as an example here. The high-risk HPV viruses can cause changes in the cells they infect within the lining of the cervix. These changes cause the cells to begin multiplying excessively, a condition referred to as cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Fortunately, CIN can be found during a routine pap test (more on those later), so it can be dealt with before it can develop into cancer.

It’s clear from those statistics that HPV can have some pretty dangerous consequences. Fortunately, there are widely available vaccinations recommended by the CDC that protect against multiple types of HPV. Gardasil, for example, provides protection against “the two low-risk HPV types that cause most genital warts, plus the seven high-risk HPV types that cause most HPV-related cancers.”

For those with a cervix, there are several methods of routine cervical cancer screening. Over the last 40 years, regular screenings have decreased the number of deaths from cervical cancer. A pap test or “pap smear” is recommended every three years starting at age 21, and screening between 30 and 65 can consist of any of three methods: a pap test every three years, an HPV test every five years, or a pap/HPV co-test every five years.

So far, there aren’t any FDA-approved screenings for HPV or cancers caused by HPV in other types of tissue, but these could become available at some point down the road. For example, anal pap tests may be able to help find abnormal/precancerous cells in anal tissue.

And there you have it—the facts on the cervix, from its functions in reproduction and childbirth to what happens when certain forms of HPV infect its epithelial cells.

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you an instructor? We have award-winning 3D products and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.

Additional Sources:

- Healthline: Common Types of Human Papillomavirus (HPV)

- Healthline: Everything You Need to Know About Cervical Cancer

- Healthline: Human Papillomavirus (HPV) and Cervical Cancer

- Mayo Clinic: Stages of labor and birth

- NIH: What are the stages of labor?

- NIH: When does labor usually start?

- Osmosis: Stages of labor - physiology

- Penn Medicine: The Three Stages of Labor