Anatomy and Physiology: The Adventures of Super Spleen

Posted on 5/30/19 by Laura Snider

You could say that the spleen has a special place in my heart (figuratively, of course).

When I was in fifth grade, my classmates and I learned about human anatomy by making videos about different parts of the body. Each student wrote their own script, while the other students served as their cast and production staff. My own video, entitled “The Adventures of Super Spleen,” featured the spleen as a superhero filtering the blood, fighting off pathogens, and saving the day. I’m pretty sure there was a macrophage named Mac in there somewhere, too.

So let’s take a look at the role the spleen plays in the circulatory and lymphatic systems—the origin story of Super Spleen, as it were.

(Cue an Adam West Batman transition to the next section.)

The Spleen in Context

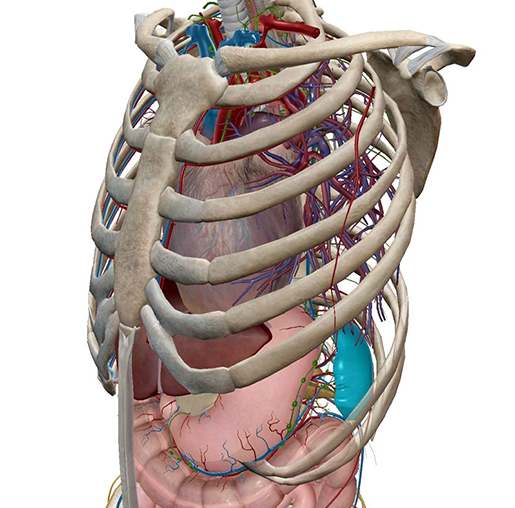

In adults, the spleen is located on the left side of the abdomen at the level of the 9th–10th ribs. It sits right under the diaphragm and slightly behind the stomach. On average, a healthy adult’s spleen weighs approximately six ounces and it’s about five inches long, three inches wide, and one and a half inches thick.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

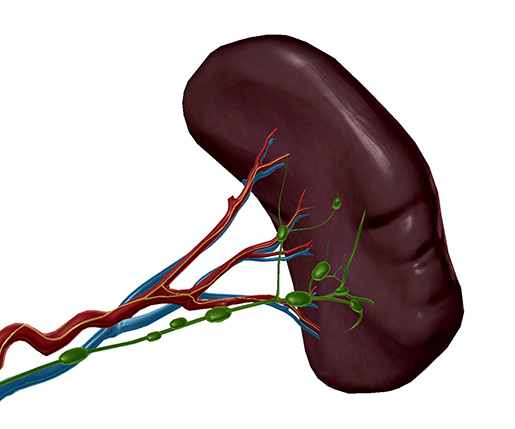

The splenic vein and artery enter and exit the spleen through its hilum, a fissure near its medial border. In the image below, you can see the nerve fibers innervating the spleen as well as the lymph nodes and vessels that connect to it. The spleen doesn’t have any afferent (incoming) lymphatic vessels, though it does have efferent ones. It gets its leukocytes (white blood cells) directly from the bloodstream.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Beneath its outer protective layer of connective tissue, the spleen contains two types of tissue: red pulp and white pulp. Red pulp contains sinuses filled with erythrocytes (red blood cells), as well as lymphocytes, platelets, and a whole bunch of monocytes (more on those later). White pulp contains lymphocytes and macrophages that line up along tiny branches of the splenic artery, ready to spring into action if they detect foreign antigens in the blood.

Here’s some fun spleen trivia! Did you know that the spleen helps people out even before they’re born, generating blood cells during the second trimester of fetal development?

Everyday Heroics: Filtering & Storing Blood

Red blood cells pass through tiny capillaries (about 3 µm wide) to reach the sinuses of the spleen’s red pulp. Healthy RBCs have no problem passing from the capillaries into the sinuses, and then heading back into the bloodstream. Tiny gaps in the endothelium of the capillaries (interendothelial slits) serve as a filter through which only RBCs that are the right size and shape can travel. Old or defective RBCs rupture as they try to make their way out of the capillaries, and if a lot of RBCs are breaking down, the spleen can become swollen and tender.

Macrophages in the red pulp clean up the remains of ruptured blood cells, digesting the RBCs’ plasma membranes and beginning the disposal process for their hemoglobin. The globin is converted to free amino acids and part of its heme group breaks down into iron, which enters the bloodstream.

In addition, the spleen helps adjust blood volume by transferring plasma from the bloodstream to the lymphatic system.

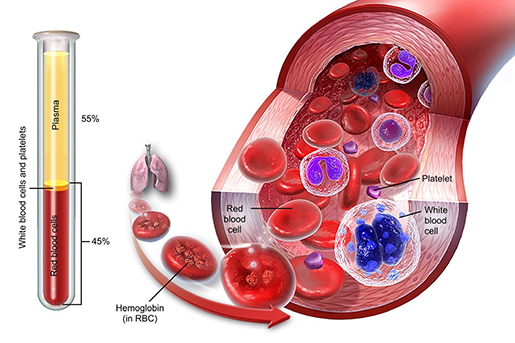

Blood composition. Image from A&P 6.

Blood composition. Image from A&P 6.

Blood storage is yet another service offered by the spleen. When expanded, its blood vessels can hold about a cup’s worth of extra blood, which can be released in case of an injury that causes significant blood loss.

Immune System...ASSEMBLE!

Picture Spiderman sitting up on a New York City rooftop, keeping an eye out for any suspicious activity. This is basically what happens in your spleen as blood moves through it. As RBCs and plasma spread through the sinuses of the red pulp, they’re in direct contact with the WBCs of the white pulp, making it easy for the lymphocytes and macrophages therein to detect intruding pathogens. These lymphocytes and macrophages can also fight infection alongside lymphocytes from other lymphatic organs.

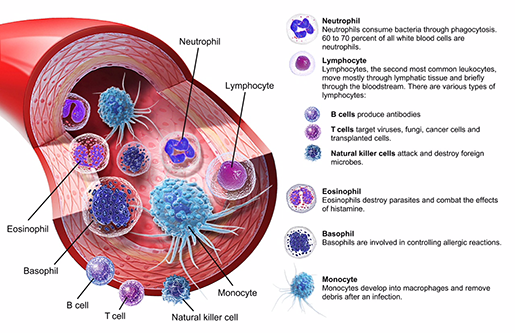

The spleen is just as good at responding to threats as it is at detecting them. It has a huge store of monocytes—white blood cells that can become macrophages or dendritic cells as needed. When infection, severe injury, or myocardial infarction occur, the hormone angiotensin II gives the orders for the spleen to deploy these monocytes out into the bloodstream. Did you know that there are more monocytes stored in the spleen than are typically in circulation in the rest of the body?

Types of WBCs. Image from A&P 6.

Types of WBCs. Image from A&P 6.

The spleen also produces proteins that help the immune system fight infection. Opsonins, for example, make phagocytosis easier by “tagging” cells that require an immune response or are ready for recycling.

This Week's Villain: Spleen Rupture

Despite the fact that it’s surrounded by a capsule of connective tissue, the spleen can rupture— and when it does, the results are potentially life-threatening.

Blunt trauma to the abdomen is the most frequent cause of a ruptured spleen. Spinal cord injury or fractures of the pelvis or ribs might co-occur with splenic rupture. Pain in the upper left abdomen is one of the symptoms of a ruptured spleen, but pain in the left chest wall and shoulder is also possible. For example, Kehr’s sign (pain in the left shoulder) happens when the phrenic nerve becomes irritated by the blood coming out of the spleen. The blood loss and drop in blood pressure caused by the hemorrhaging spleen can also lead to lightheadedness, confusion, blurred vision, fainting, and shock.

Certain diseases can cause the spleen to become enlarged and therefore more at risk for rupturing. Mononucleosis (mono), which is most commonly caused by the Epstein-Barr virus, and malaria, which is caused by parasites spread by mosquitoes, can both lead to enlargement of the spleen.

In combination with a careful physical examination, doctors typically use ultrasound and/or CT imaging to diagnose a ruptured spleen. Depending on the severity of injury to the spleen, surgery may be necessary. It is possible to repair a damaged spleen, but in some cases a full splenectomy may be required. Humans can actually live without a spleen, though doing so requires further treatment to support the immune system, such as additional vaccinations or antibiotics.

The take-home message here is that, as part of the body’s defense system and as a recycler of expired blood cells, the spleen works hard to keep the rest of the body healthy. It may not be the biggest or flashiest organ, but it’s definitely super!

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you an instructor? We have award-winning 3D products and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.

Additional Sources:

- Diagnosis and Management of Splenic Trauma

- Medical News Today: All About the Spleen

- Saladin, K (2015). Anatomy & Physiology: The Unity of Form and Function. 7th ed.

- UNSW Embryology: Cardiovascular System - Spleen Development