Posted on 3/26/13 by Courtney Smith

Open up your mouth and make a sound. I don't care what it is—scream, sing, recite the Gettysburg Address, hum your current favorite song. Let your freak flag fly.

What you're doing is phonating. Phonation is the production of vocal sound and speech. Expression through vocals may seem effortless and easy, but it actually comes from a delicate and complicated system of laryngeal muscles and ligaments. Let's take a look at them.

Oh, by the way, you can stop making that noise now.

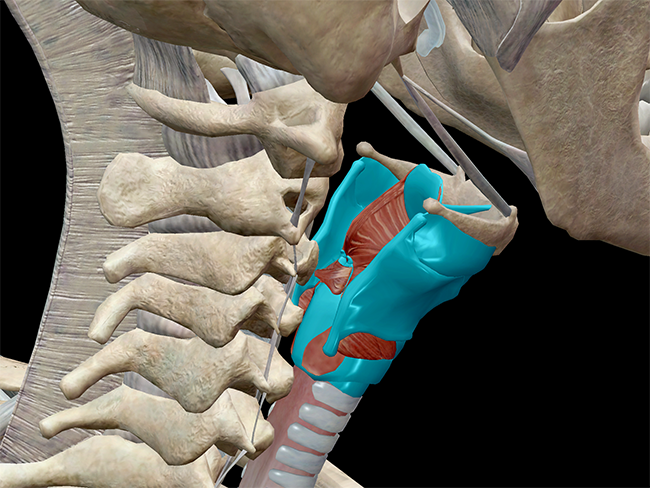

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Located between the root of the tongue and the trachea, the laryngeal skeleton is comprised of nine cartilages attached to structures of the axial skeleton: epiglottis, thyroid cartilage, cricoid cartilage, two arytenoid cartilages, two corniculate cartilages, and two cuneiform cartilages. These are connected by ligaments and moved by numerous muscles.

The movements of the laryngeal skeleton open and close the glottis and regulate the degree of tension in the vocal folds. When air passes through the folds, they produce sound. Tension levels control pitch and volume.

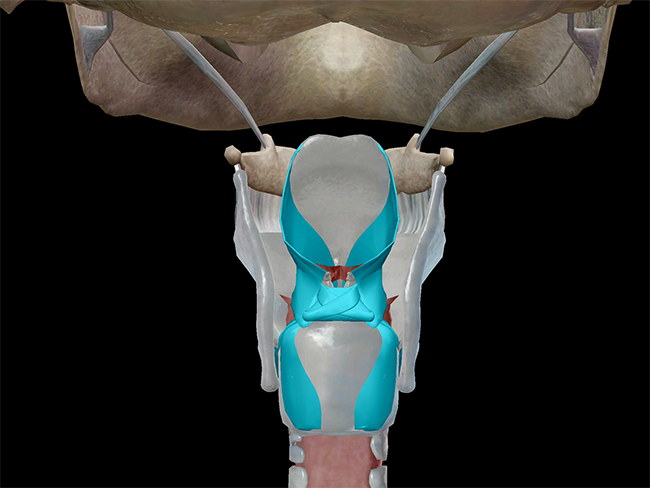

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

The laryngeal muscles are a set of muscles in the anterior neck responsible for sound production. The intrinsic muscles of the larynx function to move the vocal cartilages and control tension. They are innervated by the vagus nerve.

|

Vocalis |

Increases the thickness of the vocal cords |

|

Thyroarytenoid |

Shortens and relaxes the vocal folds |

|

Thyroepiglottic |

Depresses the epiglottis |

|

Cricothyroid |

Lengthens and stretches the vocal cords |

|

Lateral cricoarytenoid |

Closes the glottis |

|

Oblique arytenoid |

Narrows the laryngeal inlet |

|

Posterior crioarytenoid |

Separates the vocal folds |

|

Transverse arytenoid |

Closes the posterior glottis |

|

Aryepiglottic |

Depresses the epiglottis and closes off the larynx during swallowing |

Got all that? All right, let's take a look at some of the individual structures involved in phonation.

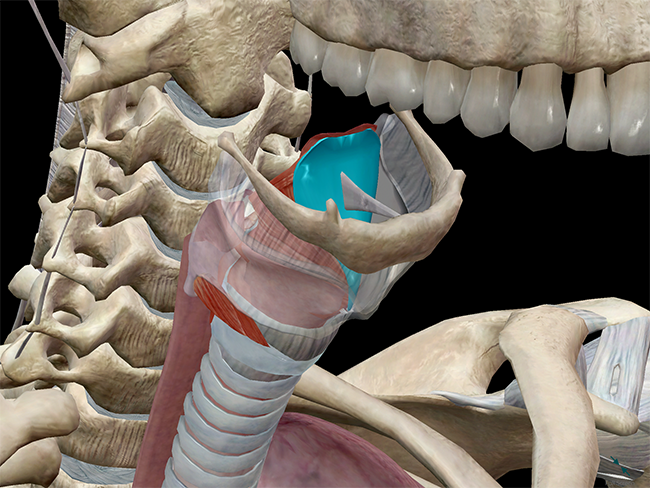

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

As I said in my previous post, I have a love–hate relationship with the epiglottis. In college, I had to take a linguistics course and glottal stops—purposely obstructing airflow while speaking to produce certain sounds (like "uh-oh")—were my sworn enemy. Using glottal stops is easy, but diagraming it into a sentence? Not so much.

The epiglottis is a leaf-shaped structure that projects upward behind the root of the tongue, in front of the entrance to the larynx. When you swallow, the aryepiglottic and thyroepiglottic muscles pull down the epiglottis to close the entry to the larynx, preventing anything from entering the trachea.

Now apply that principle to the stoppage of air. The epiglottis is pulled down to stop air from entering the trachea. For example, you tend to create glottal stops in words that end in t+vowel+n. The word "button" sounds like "butt-n" when spoken—you don't tend to vocalize the vowel. The vocal cords close sharply, the epiglottis comes down, and no air is passed.

An anatomy lesson and a linguistics lesson! You're welcome.

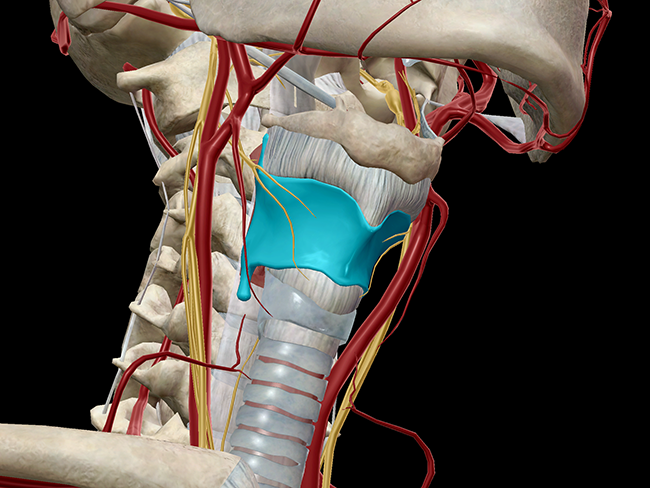

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

The thyroid cartilage is the largest of the nine laryngeal cartilages. Its main function is to protect the vocal cords, and to also serve as an attachment site for muscles and ligaments. The thyroid cartilage consists of two laminae that fuse anteriorly together and form a prominence under the skin commonly known as the Adam's apple. Men tend to have a more pronounced Adam's apple than women.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

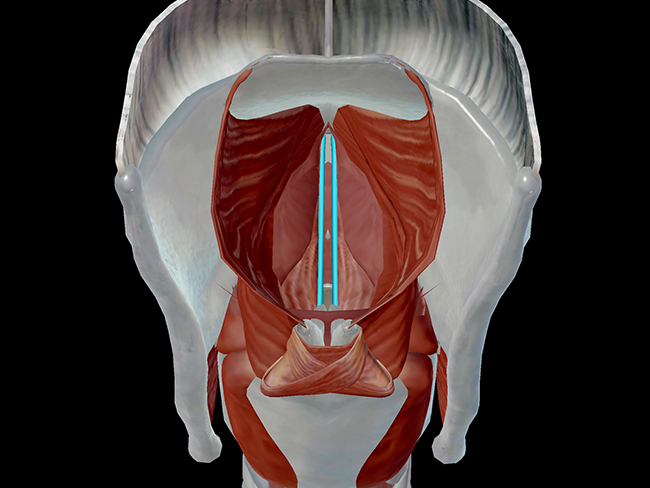

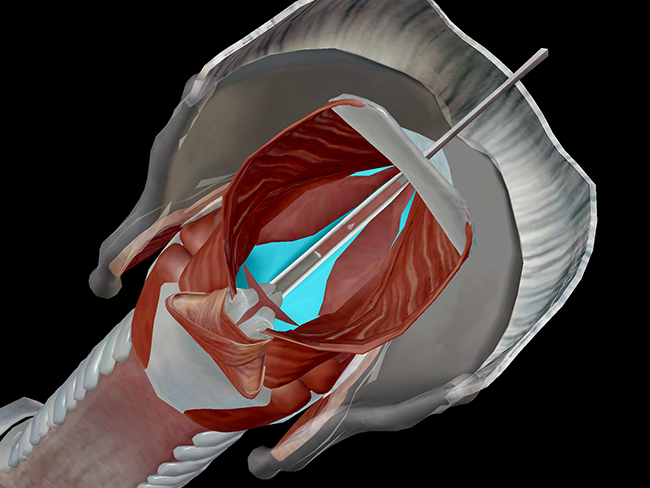

Sitting beneath the mucous membrane of the larynx are the vocal ligaments. Each ligament consists of a band of yellow elastic tissue attached to the thyroid cartilage and the vocal process of the arytenoid cartilage.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

The vocalis is an intrinsic laryngeal muscle comprised of fibers from the thyroarytenoid muscle. It runs parallel and attaches directly to the vocal ligament. It originates on the interior surface of the thyroid cartilage and inserts on the vocal process of the arytenoid cartilage. It works to tense and thicken the vocal cords, which varies tonal qualities and pitches of your voice.

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you an instructor? We have award-winning 3D products and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.

When you select "Subscribe" you will start receiving our email newsletter. Use the links at the bottom of any email to manage the type of emails you receive or to unsubscribe. See our privacy policy for additional details.

©2025 Visible Body, a division of Cengage Learning