Anatomy and Physiology: Major Components of the Digestive System

Posted on 10/26/12 by Courtney Smith

Hey, did you hear that? That rumbling sound? It was either thunder on the horizon or your tummy talking. If the skies are clear, then blame it on borborygmi. Talk about a mouthful, right? (Oh, brace yourselves for the puns about eating.)

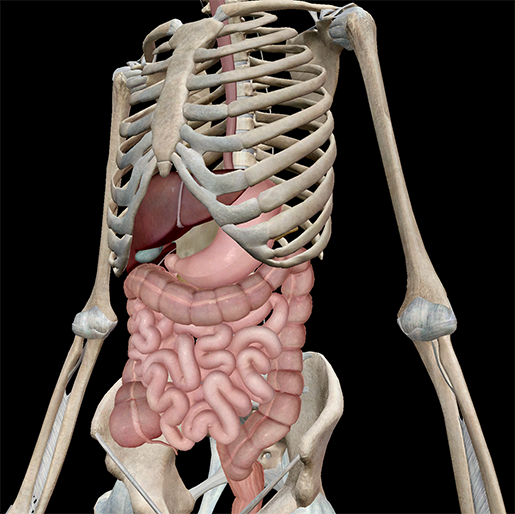

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Borborygmi are the sounds your stomach makes (aka, the stomach grumble); it usually happens when your stomach sends signals to your brain, telling your body to eat something. That's just one of many actions the digestive system engages to get nutrients into your body and waste out.

Think of eating like a train ride: whatever you injest is like a train chugging along on a long path, making pitstops before it gets to its final destination. It's a long journey for a piece of pie to go from start to finish along the 9 m (30 ft)–long digestive tract, and we're going to hit many stops, so grab a snack and let’s get started!

Stop One: Oral Cavity

Has your mouth ever "watered" when you look at something yummy? I bet it has. Your body produces extra saliva in preparation for eating. You have three sets of salivary glands: the parotids, located by the rami of the mandible; the sublingual glands, at the base of the oral cavity; and the submandibulars, halfway along the body of the mandible.

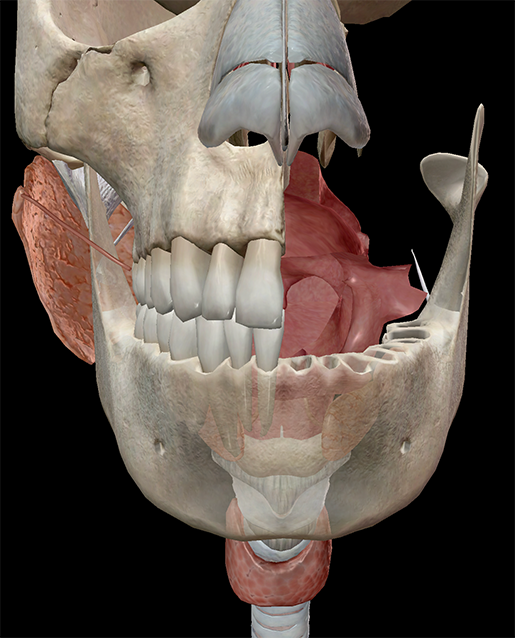

Pictured: A truly terrifying cross-section of the oral cavity and nearby anatomy). Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Whenever you put a piece of food in your mouth and chew (or masticate), these glands send saliva into the oral cavity to help break down the food. Saliva is 99% water and 1% enzymes, electrolytes, and antibacterial units.

When you eat, your food is chewed into a mass that's prime for swallowing, called a bolus. Try swallowing. Notice how your tongue presses against the roof of your mouth? That action moves a bolus to the back of the oral cavity. Each bolus needs to steer clear of the trachea and enter the esophagus. That's where the epiglottis comes in.

Stop Two: Esophagus

The epiglottis (leaf-shaped highlighted structure) acts like a trap door. Each time you swallow it lowers, preventing access to the trachea (highlighted) and thus directing a bolus into the esophagus (pink tubular structure behind trachea).

It takes about eight seconds for a bolus to move from your mouth down the long, muscular esophagus. Where the esophagus meets the stomach is the gastroesophageal sphincter. When a bolus reaches the sphincter, this ring of muscular fibers relaxes, allowing the bolus to enter the stomach.

Stop Three: Stomach

If you could see through the stomach wall and inside the stomach you would see the three muscle layers that comprise the stomach wall and the inner lining—the mucosa. Involuntary muscle contractions called peristalsis come in waves that move the muscle wall (about every eight seconds) and help break up food. The bolus that enters your stomach is broken up into a liquid called chyme.

The digestive track has a number of sphincters—ring-shaped structures formed by muscular fibers. These sphincters function like one-way valves that direct food and waste through the digestive tract. Chyme passes from the stomach, through the pyloric sphincter, and into the small intestine.

Stop Four: Small Intestine

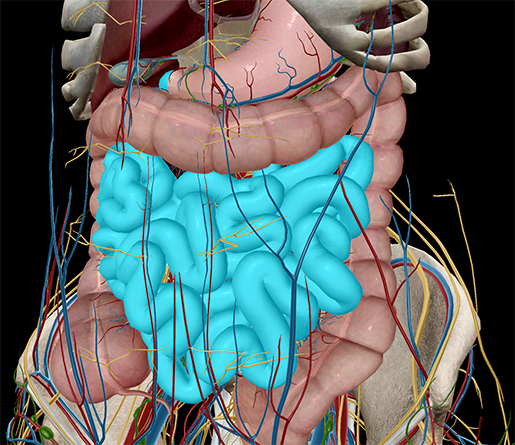

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

The small intestine is 7 m of tubular tract; its walls are lined with serous, muscular, and mucosa, which maximize surface area absorption. While chyme moves through the small intestine, most of the nutrients from whatever you ate are absorbed.

Stop Five: Accessory Organs

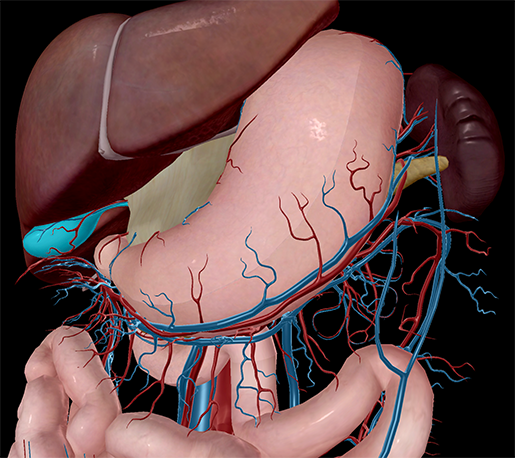

Your accessory organs secrete substances that aid in digestion. These enter the small intestine through connective ducts. The liver (large, brownish structure in image) produces bile, a fluid that aids in digesting lipids, and aids in metabolism and detoxification.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Bile is stored in the gallbladder (bulbous structure underneath liver, highlighted). The pancreas (yellowish structure) produces pancreatic juice, an important digestive fluid made of enzymes, water, and electrolytes (are you seeing a pattern to the components of digestive fluids?).

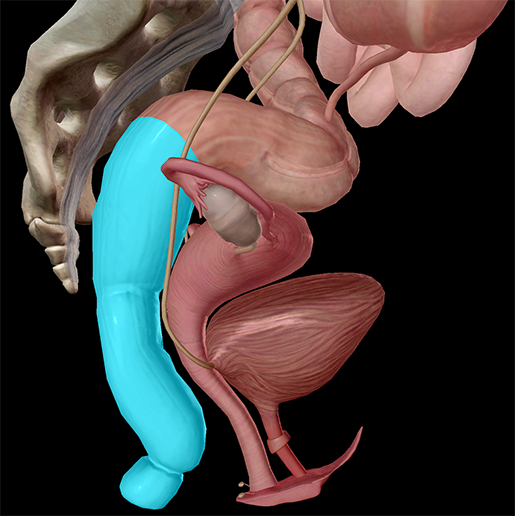

Stop Six: Large Intestine

Some nutrient absorption also happens in the large intestine, and there are different types of bacteria that break down what the body can’t do itself, but for the most part, the remnants of what you ate that make it all the way to the large intestine are going to be compacted into solid waste. Catastalsis is exactly like peristalsis, but occurs in the intestines, and it works to take the water out of waste and compact it into stool.

Last Stop: Rectum

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

We’ve come to the last stop on our journey (pun totally intended!): the rectum. It is here that solid waste gathers and is expelled from the body. The voluntary internal and voluntary external sphincters control the passage of waste out of the body.

So the next time you hear your stomach rumbling, grab yourself some chips and hitch a ride on the Food Express.

Want to experience a walk-through of the digestive system in 3D? Check out this video!

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you an instructor? We have award-winning 3D products and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.