A Tale of Kittens and Ballers: The Anatomy and Pathology of ACL Tears

Posted on 7/18/17 by Marian Siljeholm

If you’ve never had a cat or a best friend or roommate with one, you might not like cats. They possess a quiet affection and loyalty that I often find difficult to explain to my dedicated dog-owner friends, and that I myself never understood before I met Midnight.

She is a majestic 18-pound, all-black bundle of goodness, who I spotted at the Northeast Animal Shelter 17 years ago; her tiny black head peeked out at me through the tangled mass of her inky siblings, and I was in love.

Little has changed since then except both of our physical sizes, hers to a more notable and comical degree according to numerous houseguests, all of whom she immediately charms with her warm, comfortable presence and deep, throaty purr that seems to reverberate through her dog bed to the floor below (one-size-fits-all cat beds are a lie). She was essentially the Adele of kitties, in my entirely unbiased opinion.

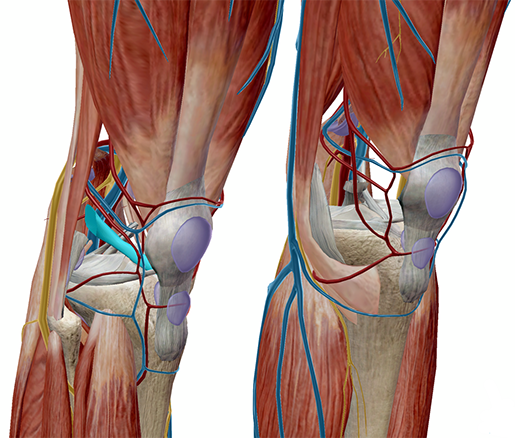

Image from Visible Body Suite.

Image from Visible Body Suite.

And yet Midnight’s bulk, which appeared remarkably quickly and stubbornly persists regardless of owner-imposed diet and exercise regimes, is always a topic discussed with love; my brother even dubbed her “low clearance” for the way her fluffy undercarriage sways just close enough to the floors to act as a gentle Swiffer duster.

I adore every inch of Midnight, and judging by the years of nights she chooses my bed, follows me to and from neighborhood playdates, and shows a supernatural ability to appear at the slightest hint of my distress, the feeling is mutual. So when she began limping, I immediately took notice, and a yowling-filled car ride later (we share mutual feelings about doctors) we found ourselves in the veterinarian’s office, Midnight voicing her discomfort as her back legs were prodded and poked.

Following plenty of patient questions, the pastel scrub–clad vet deduced that my precious Midnight had sustained an injury I had grown up believing to be reserved for athletes of the basketball player variety: she had torn her anterior cruciate ligament (ACL).

It should be noted that in felines it’s not called an ACL; she had technically torn her cranial cruciate ligament or CCL, the feline equivalent of her ACL, likely by landing awkwardly on a ligament already strained by her unusual bulk.

Spurred by a desire to understand what had happened to my beloved feline companion, and an embarrassed awareness that I had retained little from my high school basketball practice lectures and demonstrations, I decided to do some research, and as it turns out, all those cautionary testimonials were for good reason, as tearing the ACL is one of the most serious (not to mention painful) types of knee injuries. Poor Middy.

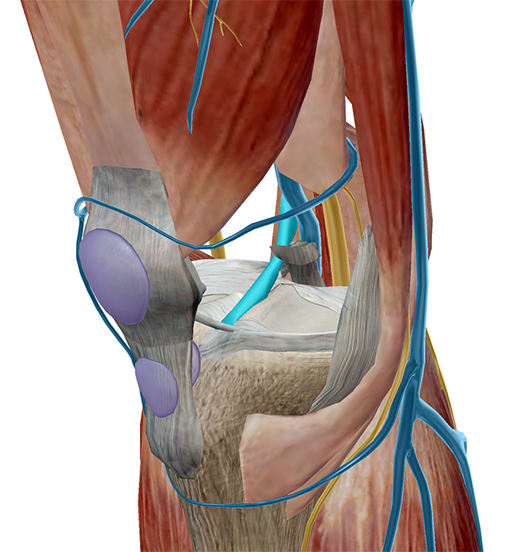

ACL without tear.

ACL without tear.

ACL with tear. Images from Visible Body Suite.

ACL with tear. Images from Visible Body Suite.

First you might ask, as I certainly did, what is the ACL? What does it do? Besides tear, apparently.

Well, let’s start with the important stuff: location, location, location! The ACL lives within the knee joint, behind the kneecap (patella), above the shinbone (tibia), and below the thighbone (femur), as one of the four central ligaments that connect the knee joint to the shinbone and thighbone.

Working together with the far less famous PCL (posterior cruciate ligament), the ACL helps keep the knee stable while rotating. More specifically, the ACL keeps the shinbone in place and prevents it from moving too far forward and away from the knee and thighbone. It also provides stability when rotating the shinbone, all very important functions when you’re using those knees to run, jump, and twist at high speeds on a breakaway layup when you’ve got five seconds on the clock and you’re down by two. Just saying.

Want to learn more about sports injuries? Check out our free "Sports Injuries 101" eBook!

So despite coach’s warnings, you’re lost in the heat of the game and you’ve forgotten everything she said about how to properly twist when you jump for the rebound. You’re lying on the court in pain, or perhaps you’re just a morbidly obese house pet who took a tumble; how can you tell the difference between torn and just sore? First, try to ignore what coach might say about “pushing through the pain.” With ACL tears, “pushing through the pain” will push you into a heap more trouble as the pain level can vary in the immediate aftermath of this particular injury, meaning that some players might be tempted to return to the game despite having trouble walking. Some other crucial indicators to be alert for are:

- Feelings of instability and inability to bear weight on the affected leg

- Increased pain accompanied by swelling of the knee joint, often within 24 hours of the tear

- During the injury itself, many athletes report hearing a “pop” sound (cringe), which is the sound of the shinbone popping out of and back into place (double cringe).

- Some also report the knee feels “less tight” or less compact than it was before; don’t let the yogis fool you, lack of tightness in a few instances is far from ideal apparently.

As a shameless abuser of Web MD, I’m thrilled to say that with this injury my penchant to latch onto the most extreme medical prognosis is actually not entirely unhelpful, as erring on the side of caution in the instance of knee injury prognosis and especially a potential ACL tear can save your knee, or at least months of extra rehab. Where you can improve on my strategy is to seek actual medical attention from a licensed professional instead of relegating your symptoms to a web browser.

If immediate medical attention is not possible, ice and elevation is highly recommended to reduce swelling, pain, and inflammation until you can get yourself to the doc. Furthermore, if putting weight on the knee is painful, do not test it, regardless of what it might do to your seasonal scoring average, as in doing so you’ll risk permanent damage that will keep you out of the game for seasons to come.

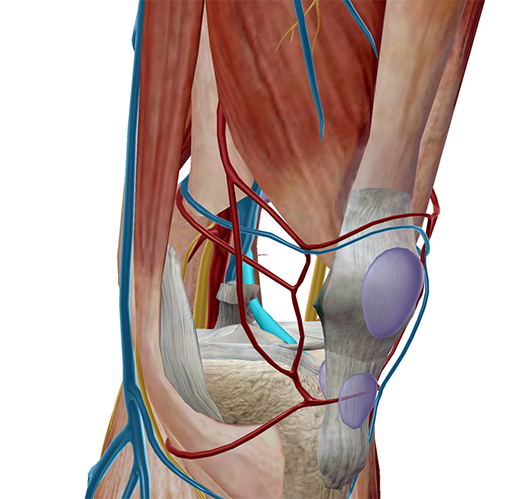

Image from Visible Body Suite.

Image from Visible Body Suite.

Once you get to the doctor, a Lachman test or an anterior drawer test, in combination with an X-ray and MRI and imaging tests, will likely be used to determine the existence and severity of your knee injury. As with many injuries, treatment for an ACL tear depends on the age of the patient and the severity of the injury; it’s safe to assume, however, that most treatments will involve surgery (gulp), a prospect that can be complicated if the patient is still growing. In that case, surgeons must be sure not to damage still “open” growth plates as they have not yet hardened (ossified) along with the rest of the bone.

Assuming skeletal maturity, the surgeon will drill a small tunnel down through the femur to reach the inside of the knee joint (drills, surgeons, and needles, oh my), then replace the torn ACL with tissue from the patient’s body (usually from the patellar tendon or hamstring) or with donated tissue. The new ACL tissue is then secured in the proper area with screws or other fixtures. In the case of a young patient, surgeons employ a slightly more complex technique involving the iliotibial (IT) band so as to spare the growth plates. Following surgery, patients will need to severely limit physical activity, and likely wear a full-leg brace as well as crutches for 4 to 6 weeks, depending on the surgeon’s prognosis. Bye-bye playoffs.

Image from Visible Body Suite.

Image from Visible Body Suite.

I had experienced the ACL lecture as a basketball player, but as it turns out, we’re far from the only population (and species) at risk. Anyone who plays a contact sport such as football, or so-called “cutting” sports such as soccer and baseball that encourage players to conduct abrupt movements such as pivoting, stopping, or turning at high speeds, are far more likely to sustain a tear.

Supplementing my (female) coach’s rant to her (women’s) basketball team, is the troubling statistic that teenage girls are 2 to 10 times more likely than boys to tear an ACL. And while I’d love to blame this fact on biologically institutionalized sexism, it’s really just the biology that drives this unfortunate reality, as girls naturally possess a few characteristics in shape, limb alignment, neuromuscular control, and hormones that render them more susceptible to a tear.

Bottom line: ACL tears are no fun for anyone, feline, female, or otherwise, so the best course of action is to prevent tears before they happen, which you can do by working certain strengthening exercises into your routine and taking other precautions both on and off the court. You’ll save a lot of pain and energy (not to mention money at the vet’s office) in addition, making your high school basketball coach proud enough to maybe even forgive you for never mastering the leftie layup. Unlikely in my case, but hey, it’s a start.

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you a professor (or know someone who is)? We have awesome visuals and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.

Additional sources:

- “Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Injuries.” KidsHealth. Ed. Alfred Atanda Jr. The Nemours Foundation, Oct. 2015. Web. 10 July 2017.