A Heated Discussion: Heat Exhaustion, Heat Stroke, and Other Heat-Related Illnesses

Posted on 6/27/22 by Laura Snider

Summer is coming. Not quite as ominous-sounding as “winter is coming,” perhaps, but summer carries a series of health emergency risks that are important to keep in mind as the weather warms up.

Whether we’re playing sports, going to the beach, or doing yard work, a lot of us find ourselves out in the heat a lot during the summer months. Our bodies usually keep us cool by sweating, but in extremely hot weather, temperature regulation becomes more difficult. When the body can’t cool itself well enough, dangerous conditions like heat exhaustion and heat stroke can result.

In this blog post, we’ll go over the signs and symptoms of heat exhaustion and heat stroke, as well as the differences between them. We’ll also talk a bit about a few other heat-related illnesses, such as sunburn, heat cramps, and heat rash.

How the body responds to heat

Before we get into the specifics of different heat-related conditions, let’s talk about how the body regulates its temperature, a process called thermoregulation.

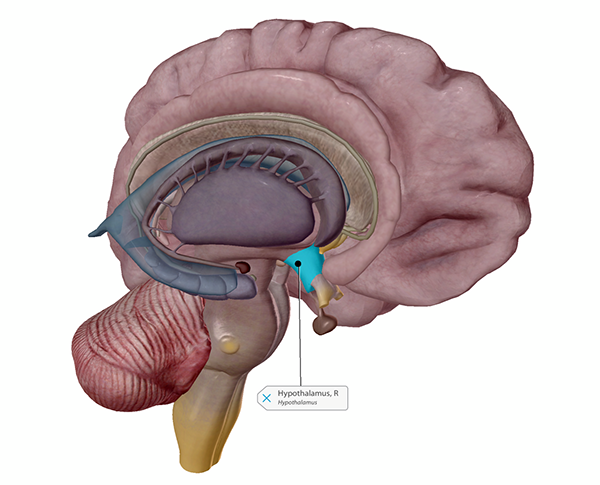

The hypothalamus has a plethora of important functions, and one of them is thermoregulation. Using input from the nervous system’s sensory receptors, it keeps track of the body’s internal temperature, and it sends signals out to the rest of the body when that temperature is too low or too high.

The hypothalamus. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

The hypothalamus. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

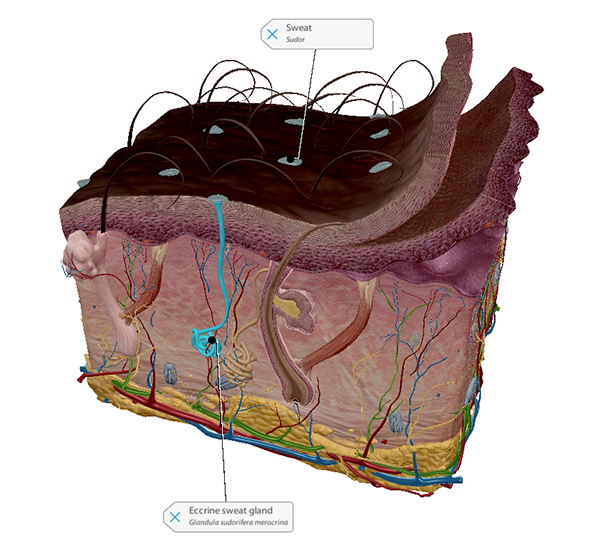

If the body’s temperature is too high, the sweat glands in the skin will release sweat, which evaporates off the skin’s surface and cools it. Blood vessels leading to the capillaries that supply the skin will also dilate, increasing blood flow to the skin and thereby allowing more heat to radiate into the outside environment (away from the body’s core).

Sweat glands and sweat. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas 2022+.

Sweat glands and sweat. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas 2022+.

A healthy human body temperature is usually around 37°C or 98.6°F. This temperature changes a tiny bit during different points throughout the sleep/wake cycle and depending on the environment and physical activity. Some people have a higher or lower “baseline” temperature than others. The body will increase its temperature in cases of infection, leading to a fever.

However, any extreme changes in body temperature pose significant risks to one’s health. Hypothermia, for example, happens when the body drops to a temperature below 35°C (95°F). Hyperthermia is a term used to refer to abnormally high body temperature. Temperatures above 42°C (107.6°F), can lead to permanent brain damage and death.

Heat cramps

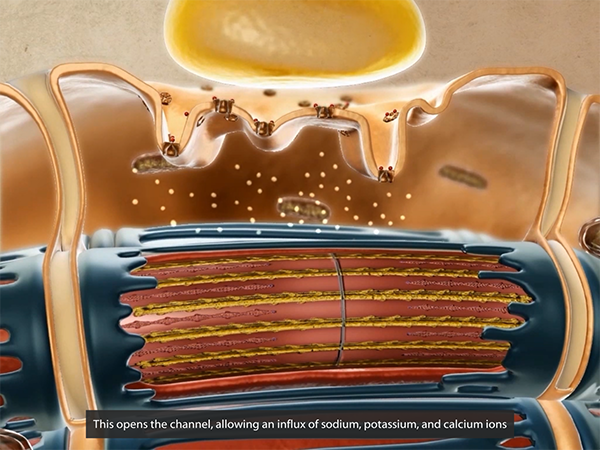

The combination of hot weather and exercise can lead to muscle cramping, especially in the legs, arms, or abdomen. Heat cramps are often an early sign of heat-related illness, and occur along with heavy sweating. Dehydration, being low on electrolytes, and not being used to athletic training in a hot environment can increase a person’s risk of developing heat cramps. Electrolytes such as sodium, potassium, and calcium, play important roles in muscle contraction.

Sodium, potassium, and calcium in muscle contraction. Animation screenshot from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Sodium, potassium, and calcium in muscle contraction. Animation screenshot from Human Anatomy Atlas.

The CDC’s advice for dealing with heat cramps is to stop physical activity, move to a cool location (a shady or air-conditioned area), and drink water or a sports drink to restore needed fluids and electrolytes. If the cramps last longer than an hour, or if a person suffering from heat cramps has preexisting heart problems or keeps a low-sodium diet, the CDC advises seeking medical help.

Heat exhaustion: time to cool down, hydrate, and see if symptoms improve

Heat exhaustion, which can escalate to heat stroke if symptoms persist for too long, is what happens when your body stops being able to cool itself adequately. It occurs in hot or hot and humid environments, often when a person is participating in physical activity. Certain medications and medical conditions can also increase the risk of developing heat-related illness (heat exhaustion or heat stroke).

The Mayo Clinic lists the following as symptoms of heat exhaustion:

- Cool, moist skin with goose bumps when in the heat

- Heavy sweating

- Faintness

- Dizziness

- Fatigue

- Weak, rapid pulse

- Low blood pressure upon standing

- Muscle cramps

- Nausea

- Headache

These symptoms may come on gradually (after spending several days in a hot environment, for example) or suddenly. Either way, it’s important not to ignore them and to start trying to cool down ASAP. According to the CDC and the Mayo Clinic, a response to heat exhaustion should include: stopping physical activity, moving to a cool place, loosening clothes (and/or removing additional layers), drinking cool water or a sports drink, and using cool cloths on the skin or taking a cool bath. Keeping an eye on someone with heat exhaustion is vital—if their symptoms don’t improve within an hour, if they are vomiting, if they lose consciousness, or if they begin to act confused or agitated, they will need medical attention right away.

Heat stroke is potentially fatal: get medical help immediately!

As the body’s internal temperature increases, so does the risk of permanent organ damage or death. Remember how vasodilation is one of the strategies the body uses to cool itself off? In heat stroke, the heart has to work increasingly hard to pump blood through those dilated vessels. Eventually, the heart just can’t keep up with that increased workload, and its ability to supply blood to the brain and other internal organs is reduced as heat stroke progresses.

High temperatures are incredibly dangerous for the brain, leading to cell death and the breakdown of the blood brain barrier (which keeps unwanted substances out of the brain while allowing oxygen and nutrients in).

One of the big differences between heat exhaustion and heat stroke is the fact that when a person is suffering from heat stroke, they stop sweating. Their skin may be hot, red, dry, or slightly damp, depending on whether they developed heat stroke as a result of exposure to an extremely hot environment or as a result of physical exertion in hot weather.

Ultimately, warning signs of heat stroke include:

- A body temperature of 40°C (104°F) or above (the CDC’s guidelines say 103°F or above)

- Changes in mental state or behavior (including confusion, agitation, or even seizures)

- A racing heart rate and rapid breathing

- Altered sweating

- Flushed skin

- Headache

- Dizziness

- Nausea/vomiting

- Passing out

Heat stroke is a medical emergency—if you suspect someone is suffering from it, get help right away (by calling 911 in the US or 999 in the UK, for example). While waiting for help to arrive, the CDC advises moving the person with heat stroke to a cool place, and keeping the outside of the body cool by sponging, misting, or spraying the person with cool water or putting them in a cool bath. A person with heat stroke might not be awake or alert enough to drink water safely on their own.

Heat and the integumentary system: heat rash and sunburn

The skin, the body’s largest organ, is what stands between the inside of our body and the world outside. When the weather gets hot, it’s what encounters UV radiation from sunlight and contains our sweat glands.

When sweat glands under the skin become blocked, heat rash can result—the trapped sweat beneath the skin causes blisters and bumps to appear. Heat rash is frequently seen in children, but adults can get it, too, especially in areas where there are folds in the skin or where clothing causes friction. Usually, heat rash resolves on its own, but it’s helpful to cool the skin and prevent sweating.

Sunburn is another risk of spending time outdoors during the summer. It can definitely occur at the same time as other heat-related illnesses, but it can happen on its own, too.

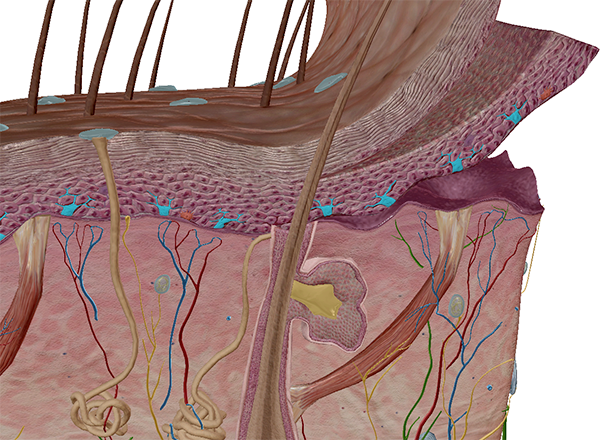

As the name indicates, sunburn is an inflammatory reaction to UV radiation from the sun, which can damage the outer layers of the skin. A mild sunburn may make skin look more pink than normal, while a severe sunburn can result in painful blisters. Some people are more prone to sunburn than others—cells called melanocytes produce melanin in the skin, and people whose melanocytes produce less of this pigment tend to be more likely to get sunburn.

To learn more about skin pigmentation, check out the new skin microanatomy models in Human Anatomy Atlas 2022+!

Melanocytes shown in skin with lighter pigmentation. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas 2022+.

Melanocytes shown in skin with lighter pigmentation. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas 2022+.

The American Academy of Dermatology and the CDC recommend the following for treating sunburn:

- Cool showers/baths to relieve pain

- Moisturizing lotion (often contains aloe)

- Taking aspirin or ibuprofen

- Not popping blisters

- Staying hydrated

- Avoiding additional sun exposure while sunburn heals

Repeated sunburns, even mild ones, increase the risk of developing skin cancer later on, so sun safety strategies like wearing broad-spectrum sunscreen, dressing in clothing that provides good coverage, and staying in the shade as much as possible are good ideas.

When it comes to staying safe in the heat, following the CDC’s hot weather tips is a great idea: stay cool, stay hydrated, and stay informed. Remaining inside during the hottest parts of the day, or exercising in an air-conditioned environment, can help prevent heat-related illnesses. For those who don’t have air-conditioning at home, many towns and cities set up heat-relief shelters when the heat becomes severe. Shopping malls and public libraries are also good places to get air conditioning for a few hours. When you’re outdoors, wearing sunscreen and lightweight, loose-fitting clothing can help you avoid skin damage and overheating. Making sure to drink plenty of water, even if you’re not exercising, is a great way to help prevent heat-related illnesses.

Keeping an eye on other people for signs of heat exhaustion and heat stroke is helpful, too, especially young children and elderly folks, who are at an increased risk for heat-related illnesses. Also, never leave another person (or pet!) in a parked car.

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you an instructor? We have award-winning 3D products and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.