Anatomy and Physiology: Parts of a Human Cell

Posted on 9/4/14 by Courtney Smith

I remember being in Mr. Farnsworth’s 7th grade science class when we first really began learning about cells. His room looked like the typical high school lab—high, hard tables with Bunsen burners and gas jets that no one was allowed to touch, and a cabinet full of dead things suspended in fluid in jars. My favorite thing about the room was the giant poster of the Triangulum Galaxy (I was, am, and always will be irrevocably fascinated by outer space) on the wall behind his desk.

But my second favorite thing was the poster depicting the inside of a cell. It hung on the far right wall, next to the chalkboard. While the image of Triangulum was exponentially smaller than the actual galaxy so we could see it in its entirety, the image of the cell was exponentially larger for the same reason. The cell was its own world—but instead of stars, gases, and dark matter, there was mitochondria, a nucleus, and cytoplasm. What that said to me was that, when you got right down to it, there wasn’t a whole lot of difference between a cell and a galaxy.

My 7th grade mind = blown.

Cells are amazing, little things, and I do mean little—cells are tiny. Under the right conditions, you might be able to see an amoeba proteus or a paramecium. To get a better sense of cell size, the Genetic Science Learning Center of the University of Utah has a fun, interactive scale. Prepare to be amazed.

There are two types of cells: prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Eukaryotes contain a nucleus and prokaryotes do not. You, dear reader, are a eukaryotic being. You are made up of trillions of eukaryotic cells, of which there are over 200 different types. Each eukaryotic cell type specializes to perform certain functions. Bone cells, for example, form and regenerate bones. Ever fracture a bone? Within days, cells called fibroblasts begin to lay down bone matrix.

To learn more about cells, check out our free Human Cell eBook!

Cells can be divided into four groups: somatic, gamete, germ, and stem. Somatic cells are all the cells in the body that aren’t sex cells, like blood cells, neurons, and osteocytes. Gametes are sex cells that join together during sexual reproduction. Germ cells produce gametes. Stem cells (you may be very familiar with this term because it’s always making headlines) are like blank-slate cells that can differentiate into specialized cells and replicate.

The genetic information within each cell acts as a sort of instruction manual, telling a cell how to function and replicate.

Why don’t we take a look at the inside of a typical cell?

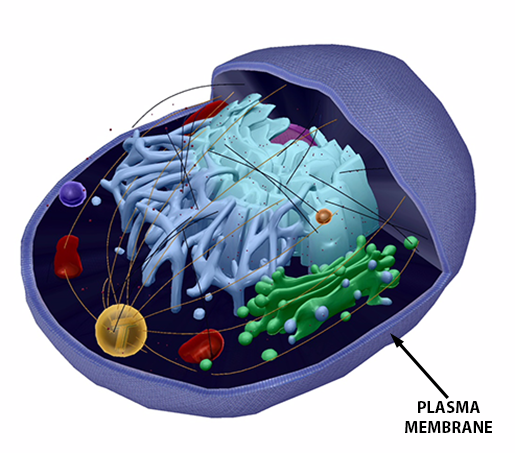

Typical Eukaryotic Cell

Image from A&P 6.

Image from A&P 6.

The plasma membrane is exactly what it sounds like: a membrane made of plasma. Membranes are structures that separate things; in this case, the plasma membrane of a cell separates its interior from the environment around the cell. It’s not impenetrable, however, as it will selectively let certain molecules enter and exit.

Organelles are the structures within the plasma membrane. Each organelle has a specialized function. They’re called organelles because they act as a cell’s organs.

Intracellular fluid, or cytosol, is the liquid found inside a cell. While most of its makeup is water, the rest isn’t very well understood. Once thought to be a simple solution of molecules, it’s organized on a multitude of levels.

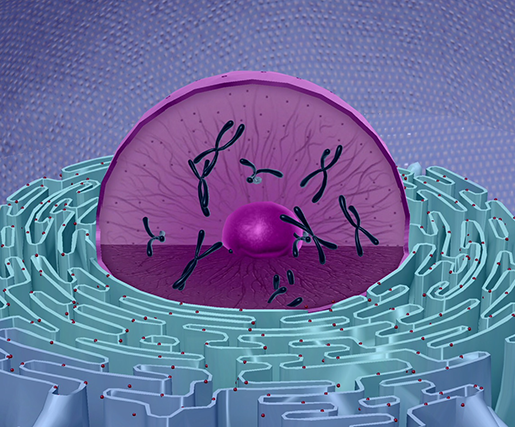

Image from A&P 6.

Image from A&P 6.

The nucleus is a large organelle that contains the cell’s genetic information. Most cells have only one nucleus, but some have more than one, and others—like mature red blood cells—don’t have one at all. Within the nucleus is a spherical body known as the nucleolus, which contains clusters of protein, DNA, and RNA. The genetic information of the cell is encoded in the DNA. The nucleus serves to contain the DNA and transcribe RNA, which exits via pores in the nuclear membrane.

Presenting: The Organelles

While all the parts of a cell are important, here are some of the most recognizable.

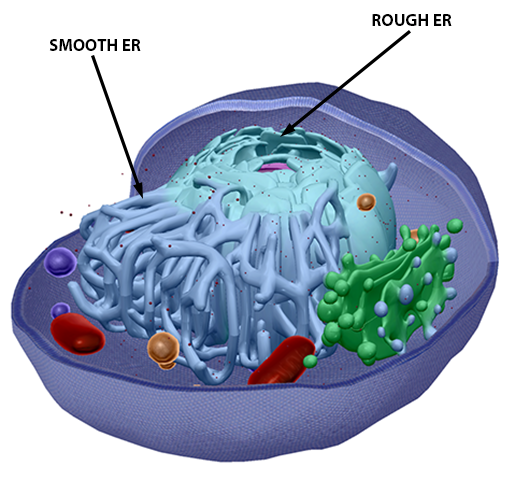

Endoplasmic Reticulum

Besides being very fun to say, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a network of membrane-enclosed sacs in a cell that package and transport materials for cellular growth and other functions. There are two types of ER: smooth and rough.

Image from A&P 6.

Image from A&P 6.

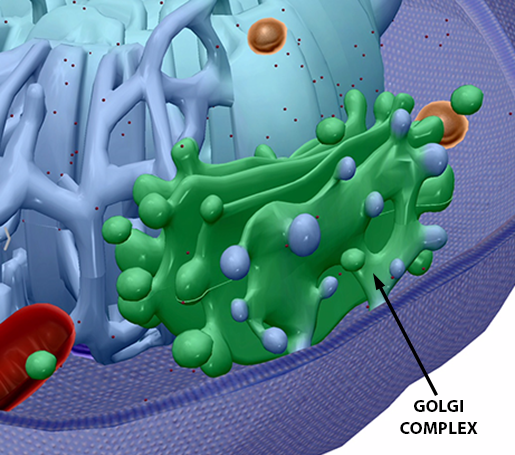

Golgi Complex/Apparatus

Like the ER, the Golgi complex (or apparatus) is an organelle that packages proteins and lipids into vesicles to be transported.

Image from A&P 6.

Image from A&P 6.

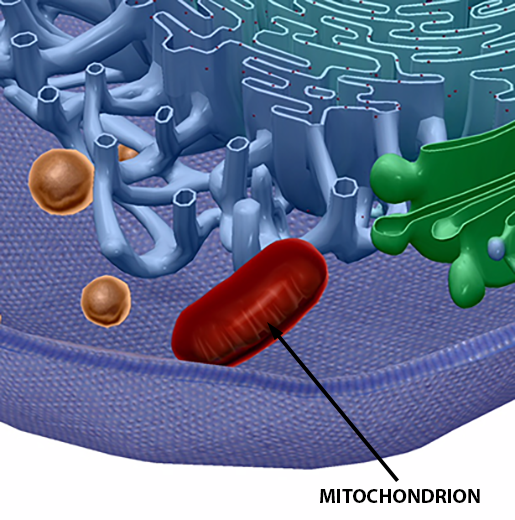

Mitochondria

“A human being is a whole world to a mitochondrion, just the way our planet is to us. But we’re much more dependent on our mitochondria than the earth is on us. The earth could get along perfectly well without people, but if anything happened to our mitochondria, we’d die.” —A Wind in the Door by Madeleine L’Engle (1973)

Image from A&P 6.

Image from A&P 6.

While Ms. L’Engle’s concept of mitochondria was more fiction than science (as far as I know, mitochondria don’t talk!), it opened my ten-year-old eyes to the wonders of our bodies. Before Mr. Farnsworth’s cell poster, there was the Time Trilogy.

Mitochondria can number anywhere in the hundreds to the thousands, depending on the cell. They are known as the “power plant” of the cell, providing the main source of energy. Through aerobic respiration, mitochondria generate most of the cell’s adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Active cells in the muscles, liver, and kidneys have a large number of mitochondria to support high metabolic demands.

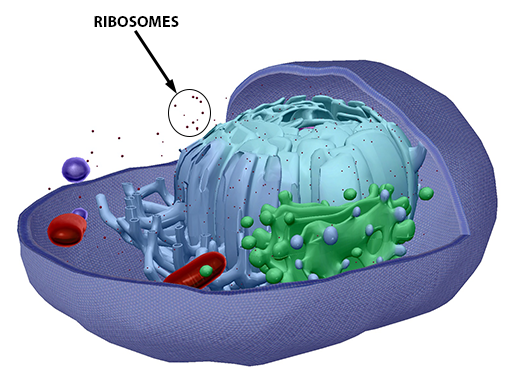

Ribosomes

Image from A&P 6.

Image from A&P 6.

Either floating freely in the cytosol, bound to the ER, or located at the outer surface of the nuclear membrane, ribosomes are plentiful within a cell. Ribosomes contain more than 50 proteins and a high content of ribosomal RNA. Their primary function is to synthesize proteins, which are then used by organelles within the cell, by the plasma membrane, or even by structures outside the cell.

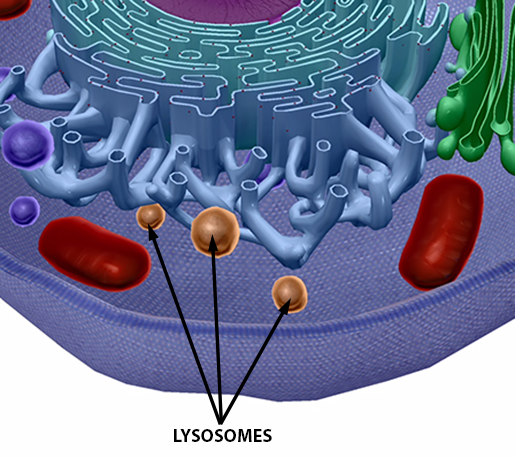

Lysosomes

Image from A&P 6.

Image from A&P 6.

These little guys are like the garbage disposals of a cell. Lysosomes contain acid hydrolase enzymes, which break down and digest macromolecules, old cell parts, and microorganisms. They originate by budding off of the Golgi complex.

There are more structures and functions within a cell (like, a lot more) than are listed here, but that’s a post for another day!

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you an instructor? We have award-winning 3D products and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.

Related Posts:

- Anatomy and Physiology: Medical Suffixes

- Anatomy and Physiology: Anatomical Position and Directional Terms

- Anatomy and Physiology: Five Cool Facts about the Middle and Inner Ear