4 Interesting Medical Stories From US Presidential History

Posted on 2/17/20 by Laura Snider

From George Washington’s dentures to Grover Cleveland secretly getting surgery on a yacht, the annals of American history hold all sorts of interesting medical stories. Since it's Presidents' Day, we figured it would be fun to share some of these weird tales about past US presidents!

1. Washington's fake teeth weren't made of wood

The story of George Washington’s various sets of dentures is a fascinating one.

Suffering from severe gum disease and tooth decay throughout his life, Washington’s first tooth extraction was in April 1756, when he was 24 years old. Records indicate that he frequently purchased dental hygiene tools and required numerous extractions of painful teeth.

Eventually, false teeth could no longer be attached to his existing teeth with wire, and in 1789 (the year he was inaugurated), he only had one remaining natural tooth. Washington’s dentist, John Greenwood, created his first full set of dentures (he would have a total of four) with a hole for that last tooth.

A healthy set of teeth and gums. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

A healthy set of teeth and gums. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

All in all, Washington’s different sets of dentures contained human teeth (both his own and those from other people), cow teeth, horse teeth, ivory, lead-tin alloy, copper alloy, and silver alloy.

Wearing the dentures was no picnic. Springs were used to keep the dentures inside Washington’s mouth, which couldn’t have been comfortable. In combination with the fact that he had significant gum loss, the spring-anchored dentures also meant that he couldn’t open his mouth very much, or the dentures might fall out.

So why is the myth that Washington had wooden teeth so popular? Perhaps people mistakenly assumed the dentures were made of wood because they became stained over time—Washington frequently drank wine with his dentures in, which his dentist scolded him for.

Fun bonus fact! Greenwood removed George Washington’s last tooth in 1796. Today, that tooth, as well as the lower half of a set of Washington’s hippopotamus-ivory dentures, is housed at the New York Academy of Medicine. The only remaining complete set of Washington’s dentures is on display at Mount Vernon, the first president’s Virginia home.

2. Pneumonia probably didn't kill William Henry Harrison

Most people know William Henry Harrison as the president who spent the shortest amount of time in office—only 30 days. You might also remember him from history class as the president whose campaign slogan was “Tippecanoe and Tyler, Too!” (His vice president was John Tyler.)

The traditional narrative of President Harrison’s untimely death goes like this. On March 4, 1841, he gave a lengthy inaugural address in wet and freezing weather, without wearing a coat, hat, or gloves. He caught a cold, which developed into pneumonia, and the complications of that pneumonia killed him. (Note that despite the fact that being outside in winter without a coat isn't the best idea, a virus still needs to be involved for a cold to occur!)

Sounds pretty reasonable, right? Well, scientists from the University of Maryland argued in a 2014 paper in Clinical Infectious Diseases that there’s more to the story. Their analysis of the case summary written by Harrison’s doctor, Thomas Miller, points to a different cause of death: enteric fever (typhoid or paratyphoid fever).

While it’s true that the president did demonstrate a number of symptoms consistent with those of pneumonia (fever, trouble breathing, and coughing up sputum that contained blood), it was gastrointestinal symptoms—constipation and severe pain in his right side—that originally motivated him to seek treatment from Dr. Miller. Though Harrison was given many enemas and laxatives, the condition of his bowels only worsened, leading to bloody stool and diarrhea.

The researchers argue on the basis of these gastrointestinal symptoms that Harrison was suffering from enteric fever, not pneumonia. Enteric fever often does manifest with respiratory symptoms, which may explain why Dr. Miller believed Harrison had pneumonia in combination with “congestion of the liver.” Throughout his treatment, Harrison also suffered from a slow pulse, which the study authors identify as another hallmark of enteric fever.

How did the president contract this deadly disease? Enteric fever is caused by infection by Salmonella typhi or S. paratyphi, both of which can be transmitted via human feces.

The small and large intestines. Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

You can probably see where this is going. Given that Washington D.C. didn’t have a sewer system until the 1850s, the waste management situation there was pretty nasty. The springs that supplied water to the White House were in serious trouble—they were located only a few blocks from a “night soil depository,” where waste from D.C.’s residents was taken after being collected. Thus, it’s highly likely that Harrison (and perhaps a few other antebellum presidents) became ill from drinking water contaminated with human waste.

While this may not be a particularly “fun” fact (because let’s face it—there’s nothing fun about typhoid fever), it’s certainly a fascinating tale. It’s also proof that in science, just as in most other fields, hindsight is 20/20.

3. Alexander Graham Bell tried to save James Garfield's life with a metal detector

You may know that on July 2, 1881, a lawyer named Charles Guiteau shot President James Garfield at the Baltimore and Potomac railway station. What you may not know is that, although Garfield’s death was ultimately a result of that attack, he spent 80 days in agony while his doctors tried to locate and remove the bullet that had lodged itself just below his pancreas.

Despite their efforts, the doctors’ attempts at treatment likely weren’t very helpful. Proper sanitation techniques like hand washing and sterilizing instruments were not yet the norm, which means that the medical team treating Garfield was probing his wounds with dirty hands and medical equipment. (Gross.)

The man in charge of Garfield’s treatment, Dr. Doctor Willard Bliss (yes, his first name really was Doctor), called in Alexander Graham Bell, the inventor of the telephone, to try and find the bullet.

Bell applied his knowledge of electromagnetism to the problem and invented the world’s first medical detector. The basic principle behind his invention was that “a metallic object near an inductor changes the value of the inductance,” and this change in induction could be reflected in changes in an audio signal that the user of the machine could hear through a telephone receiver.

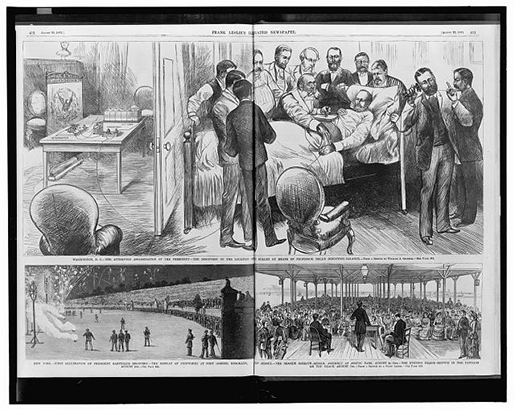

The top panel of the image set below shows Bell using his metal detector. In the picture, Bell’s assistant is moving a coil over Garfield’s stomach, and Bell is listening through a telephone receiver for any changes in the audio signal.

Illus. in: Frank Leslie's illustrated newspaper, v. 52, no. 1351 (1881 August 20), pp. 412-413. Downloaded from the Library of Congress.

Illus. in: Frank Leslie's illustrated newspaper, v. 52, no. 1351 (1881 August 20), pp. 412-413. Downloaded from the Library of Congress.

Unfortunately, Bell’s metal detector didn’t find the bullet.

Garfield’s doctors continued with all manner of unpleasant treatments, but eventually, he passed away. Records indicate that “the assigned causes of death include a fatal heart attack, the rupture of the splenic artery, which resulted in a massive hemorrhage, and, more broadly, septic blood poisoning.” Garfield died on September 19, 1881, and the assassin was hanged for his crimes in June 1882.

If you’re curious about how the doctors tried (and failed) to save Garfield, I’d highly recommend this episode of the Science VS podcast—it’s what first brought the story to my attention!

4. Grover Cleveland had secret surgery to remove a tumor

“Secret yacht surgery” may sound like the name of an indie band, but it’s also what Grover Cleveland, the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, had in 1893 to remove a tumor from the roof of his mouth.

(Want to know another interesting Grover Cleveland fact? His first name was actually Stephen, but he went by his middle name.)

In May of 1893, Cleveland noticed a bump on the roof of his mouth, near the molars on his “cigar chewing side,” and by June it had grown substantially. When he went to his doctor, he received a cancer diagnosis and a recommendation to have the tumor removed.

So, why didn’t Cleveland have the tumor removed somewhere reasonable, like a hospital? He was under the impression that requiring surgery for cancer would make him look weak and could send the country into a panic. Numerous other US presidents—including Wilson, Harding, Kennedy, and Reagan—would keep their own medical conditions or procedures quiet for similar reasons.

Cleveland declared that he was going on a fishing trip from New York to Cape Cod, and the surgery was conducted on his friend’s yacht, the Oneida. It took six surgeons ninety minutes to remove the tumor, as well as five of Cleveland’s teeth and portions of his left jawbone and hard palate. Fortunately for Cleveland, everything went well and there was no external scarring—the cover story told to the public was that he’d needed some teeth removed following a toothache.

When a journalist named E.J. Edwards published a story about the surgery, Cleveland discredited him. However, William Williams Keen, one of the doctors who’d done the procedure, wrote about the surgery in a 1917 article.

Cleveland passed away as the result of a heart attack in 1908, at the age of 71.

Hooray for modern medicine!

If these crazy president stories show us anything, it’s that medical care and public health have come a long way since the 18th century.

First of all, dentures today are much more comfortable, and dental implants are also a good option for tooth replacement—and they’re not cow teeth or other people’s teeth, which is definitely a plus.

Modern plumbing and sewer systems keep waste far away from streets and water sources, so typhoid is pretty rare nowadays in developed nations. In addition, people traveling to regions where typhoid is more common can get vaccinated, although there is no vaccine for paratyphoid fever, so that’s still a risk for travelers.

And lastly, I’m sure it goes without saying how great it is that today’s medical professionals wash their hands and use sterile equipment. Fortunately, thanks to champions of germ theory like Louis Pasteur, Robert Koch, and Joseph Lister, regular disinfecting practices eventually became the norm.

(PS: If you’re interested in learning more about the history of these practices, you can also check out the story of Ignaz Semmelweis, a mid-19th century proponent of handwashing.)

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you an instructor? We have award-winning 3D products and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.

Additional Sources:

- Algeo, Matthew. (2011) The President is a Sick Man.

- Mental Floss: Did William Henry Harrison Really Die of Pneumonia?

- Washington Post: The White House killed William Henry Harrison