4 Body Parts to Be Thankful For

Posted on 11/19/21 by Sarah Boudreau

When it comes to the body, some organs get more credit than others. We have so many songs and metaphors about lungs, guts, and veins, and we even spend a whole day in February celebrating the heart— but what about everything else?

Today, we’ll give thanks to four underrated body parts.

1. The Spleen

In a popularity contest among all the organs, the spleen probably wouldn’t end up on the podium. No characters in The Wizard of Oz would ever sing “If I Only Had a Spleen,” but the spleen does several jobs to keep your body functioning at its best.

The spleen is located on the left side of the abdomen, beneath the diaphragm. It is the largest lymphoid organ; the average spleen weighs about six ounces and measures five inches long, three inches wide, and one and a half inches thick.

GIF from Human Anatomy Atlas.

GIF from Human Anatomy Atlas.

As blood moves through the spleen, it detects antigens and sends its monocytes into the bloodstream to take care of the problem. The outside of the spleen consists of a layer of connective tissue, and the inside contains red pulp and white pulp, two types of tissue that fulfil different functions.

Red pulp contains:

- Erythrocytes (red blood cells)

- Lymphocytes

- Platelets

- Monocytes

To get to the red pulp’s sinuses, red blood cells travel through capillaries. Broken red blood cells filter through interendothelial slits, which are gaps in the endothelium of the capillaries. Microphages in the red pulp act as a cleanup crew, breaking down the broken red blood cells’ plasma membranes and beginning the disposal process for hemoglobin.

White pulp contains:

- Lymphocytes

- Macrophages

White pulp makes up about a quarter of the spleen and plays an important role in the body’s immune response. When the white pulp senses antigens in the blood, it triggers the production of antibodies to fight them off.

But wait—that’s not all! The spleen transfers plasma from the bloodstream to the lymphatic system and also can store about a cup of blood, which comes in handy in cases of blood loss. It also produces proteins that aid the immune system in fighting infection.

Blunt trauma to the abdomen can rupture the spleen—and a ruptured spleen can be fatal. Surgeons sometimes repair minor tears, but the entire spleen is usually removed during surgery. You can live without your spleen, but your body is more vulnerable to bacteria, so antibiotics and additional vaccinations are sometimes necessary.

Thanks, spleen, for multitasking better than I can!

2. The Mandible

The mandible, also known as the jaw bone, is like the Incredible Hulk of the facial bones: it’s the largest and strongest. The mandible is also the only movable bone in the skull. The mandible works together with the tongue and saliva to perform mastication, also known as chewing. Like breathing, mastication is an automatic movement—we don’t have to think about it, so we might not appreciate what the mandible does for us until something goes wrong.

The mandible is a symmetrical bone with two major parts, the body and the ramus. The body is horseshoe-shaped, with sixteen cavities for teeth.

The mandible has one ramus on either side, which are positioned at almost ninety degree angles from the mandible body. On the top of each ramus sit the coronoid and condylar processes, which, combined with the temporal bone, create the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). The masseter, temporalis, medial pterygoid, and lateral pterygoid muscles are responsible for moving the mandible up and down and side to side.

GIF from Human Anatomy Atlas.

GIF from Human Anatomy Atlas.

The mandible is the second bone to ossify in utero (the number one spot belongs to the clavicle). However, at birth, the mandible consists of two separate bones connected by cartilage. The bones fuse at age 1-2. The mandible keeps changing throughout life—tooth formation causes changes in dimensions, and old age changes the angle and size of the mandible.

When the mandible does not fuse completely during early childhood, it creates a fissure. The soft tissue over this fissure sinks in, creating a cleft chin. Cleft chins are often an inherited trait and are more common in men.

The mandible is one of the most often-fractured facial bones. Usually caused by a car accident or a physical altercation, a broken jaw is frequently accompanied by other injuries like lacerations or head injuries. The mandible fractures in multiple places about 50% of the time.

Some facial fractures, like a broken nose, heal fine on their own, but mandible fractures can sometimes require surgery. The presence of teeth can complicate things: people with wisdom teeth have a higher risk of infection, and children with mandible fractures may have damage to their permanent teeth.

TMJ disorders affect the temporomandibular joint and can be caused by things like improper bite, arthritis, and tooth grinding. The muscles and ligaments around the joint become inflamed, causing symptoms like jaw pain, earaches, and a clicking or grinding sound when you move your jaw.

Thanks, mandible, for making it possible to gobble down Thanksgiving dinner!

3. The Epiglottis

The next structure on our tour of thankfulness is the epiglottis! Like the mandible, the epiglottis is an important part of eating. It is the flap of tissue that keeps food from entering the trachea.

The epiglottis is part of the laryngeal skeleton, the skeleton of the voice box. The larynx contains the folds of tissue known as the vocal cords, the vibration of which makes speech and song possible. Though the epiglottis can be used in speech, its primary function is to keep food and liquids from entering the trachea.

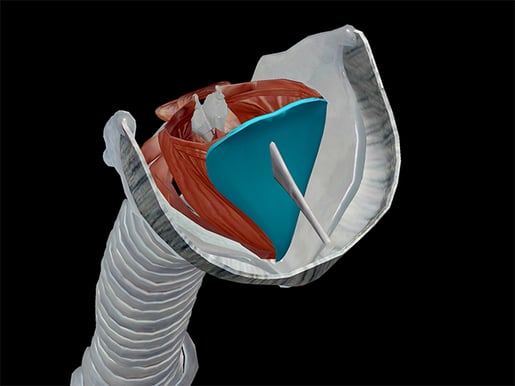

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

When you swallow, your larynx rises and the epiglottis closes over the trachea like a trash can lid. If particulates get in, the cough reflex is triggered, and air is forced out of the lungs to push the interloper upwards.

Epiglottitis, inflammation of the epiglottis, can be life-threatening—particularly to children. Swelling can block the airway more easily, as a child’s epiglottis is located more anteriorly and is less rigid than an adult’s. Signs and symptoms in children tend to appear quickly and worsen within hours.

Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib) is the most common cause of epiglottis in children. Hib disease can also cause pneumonia, bacterial meningitis, and other infections. Delivered over 3-4 doses, the Hib vaccine was first released in 1985 and has continued to be refined. Thanks to the vaccine, cases worldwide have decreased substantially, and Hib has nearly been eradicated in industrialized countries.

The Hib vaccine is actually one of those recommended for people who have their spleens removed and need additional doses to keep their immune systems up to par.

Thank you to the epiglottis for keeping our tracheas safe, and thank you to the Hib vaccine for protecting us from Hib disease!

4. The Nasolacrimal Apparatus

Last but not least, let’s show our thanks to the nasolacrimal apparatus: the system of lacrimal glands, lacrimal sacs, and ducts that is responsible for keeping our eyes lubricated.

Your lacrimal glands produce 15 to 30 gallons of tears every year. Tears are more than just salt water: they are a mixture of water, fatty oil, and over 1500 kinds of proteins.

There are three types of tears: basal tears, reflex tears, and emotional tears. Basal tears are your everyday eyeball lubrication tears; a layer of tears acts as an extra barrier for the cornea. Reflex tears occur when external stimuli like smoke irritate the eye. Emotional tears happen when, well, you get emotional. Emotional tears may occur strictly as a tool for social bonding, but the exact reason behind them remains a mystery.

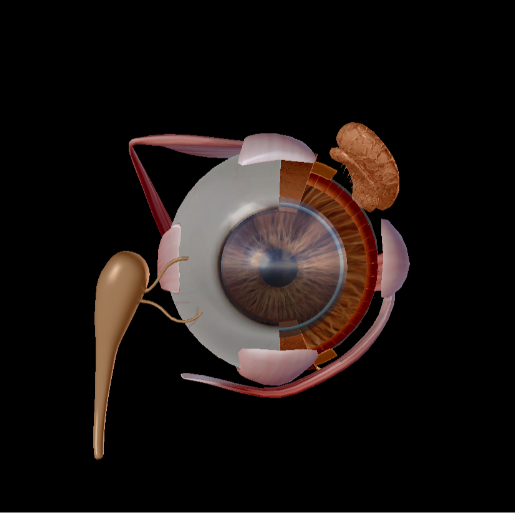

Tears move through the excretory lacrimal ducts onto the surface of the eye, where they are distributed through blinking. Here, they keep our eyes safe from particulates and debris.

Each eyelid has two small holes called the lacrimal punctum through which tears make their exit into the lacrimal ducts. The lacrimal ducts shuttle tears from the eye to the lacrimal sac, where they collect before draining to the nasal cavity.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Image from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Have you ever put in eyedrops and felt like you could taste them? That’s because they have drained into the nasal cavity and down your throat.

A tear duct blockage can be caused by a variety of factors, including infection and injury. A blockage means that the tears cannot drain into the nasal cavity correctly, and since the tears build up on your eyes, they can make the eyes more susceptible to bacteria and inflammation.

About 6% of infants are born with at least one blocked tear duct, but since newborns do not produce tears, it is not always noticeable until they are several weeks old. The culprit in this case is usually a thin membrane that covers the lacrimal ducts, and it usually resolves on its own.

Thanks, nasolacrimal apparatus, for always being there for me when I’m feeling down… and when I'm chopping onions.

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you a professor (or know someone who is)? We have awesome visuals and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.