3 Creatures that Confused Darwin

Posted on 9/16/22 by Sarah Boudreau

When a 22-year-old Charles Darwin, fresh from studies at Cambridge, left on a voyage to circumnavigate the globe, nobody expected much.

In fact, Darwin was practically an afterthought. The HMS Beagle was bound for a surveying voyage; its purpose was to take measurements, correct longitudinal measurements, and chart the southern coasts of South America. Having a naturalist on board was hardly a priority, and Darwin had no formal training. He was even considered a passenger rather than an employee, as the ship’s captain, Robert FitzRoy, came from the aristocracy and wanted a gentleman on board to dine and chat with.

The voyage proved to be massively influential to Darwin and to science itself. He once wrote that “The voyage of the Beagle has been by far the most important event in my life and has determined my whole career.”

The theory of evolution spelled out in Darwin’s 1859 book On the Origin of Species was formed through Darwin’s observations on the HMS Beagle. The finches of the Galapagos are the most well-known of these observations; their different beak shapes helped him develop ideas about natural selection. However, this was a five-year journey, and the HMS Beagle journeyed to far more places than just the Galapagos. What about the other animals he saw?

Let’s crack open our history books and talk about three remarkable animals that Darwin came across in his travels that challenged him to think in new ways about the natural world.

1. Fossilized ground sloths

Before we get to Darwin, let’s take a step back and talk about extinction. As one writer put it, “Extinction may be the first scientific idea that children today have to grapple with”: any dinosaur-obsessed little kid can explain the basics of mass extinction events. However, extinction wasn’t fully acknowledged by the scientific community until the early 1800s.

It’s worth mentioning that some Native American tribes understood extinction prior to these developments, having discovered dinosaur fossils on their land. In fact, the Delaware, Shawnee, and Piegans referred to mastodon fossils as “the Grandfather of the Buffalo.”

When European naturalists saw fossils of extinct species, they found a living counterpart to assign instead—for example, they assumed that mammoth fossils found in Italy were the bones of elephants Hannibal brought as part of his invading army. The ocean was mostly unexplored, which made it a great scapegoat: if you couldn’t figure out what animal the bones belonged to, it was probably an animal that lived somewhere in the murky depths.

Denial of extinction was tied to their religious beliefs. Most Europeans believed that the world was made perfectly with no room for error, so it was a preposterous idea that species could go extinct. After all, extinction is a pretty big error!

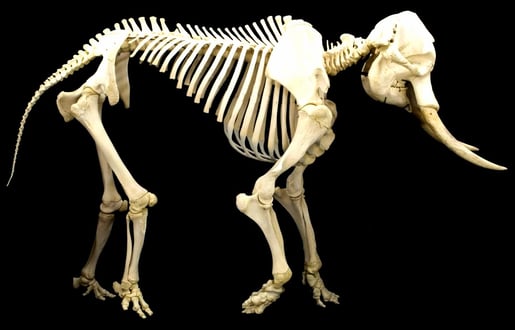

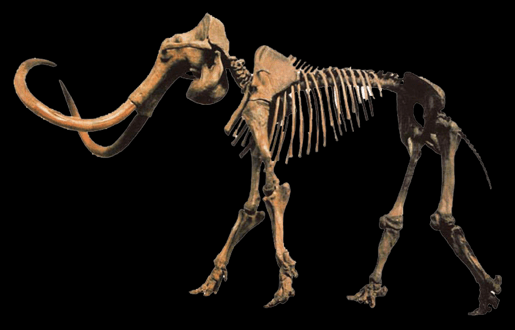

Several thinkers talked around the idea of extinction, but French naturalist Georges Cuvier set the record straight in 1796. Through dissecting specimens and analyzing their teeth, Cuvier ascertained that African and Asian elephants were different species. Then, he started to analyze fossils that everyone had assumed were ancient elephants. From this analysis, he proved that the fossils were from two species: the mammoth and the mastodon. Because mammoths and mastodons were separate from the elephants that still roamed the earth, and no living person had ever seen a mastodon or a mammoth, Cuvier made a solid case that extinction was real.

African elephant skeleton (top) and mammoth skeleton (bottom) from Wikipedia Commons.

African elephant skeleton (top) and mammoth skeleton (bottom) from Wikipedia Commons.

Only 35 years after Cuvier’s mammoth findings (pun intended), Darwin set forth on his journey aboard the Beagle. In September 1832, almost a year into the voyage, the ship docked at Punta Alta, Argentina, and Darwin spent several days exploring the area. Here, he spotted an outcropping of rock containing fossilized shells and bones. After spending three hours chipping away at the soft rock, he returned to the ship late at night with a fossilized jaw in tow.

His first impression was thus: “As far as I am able to judge, it is allied to the Rhinoceros.”

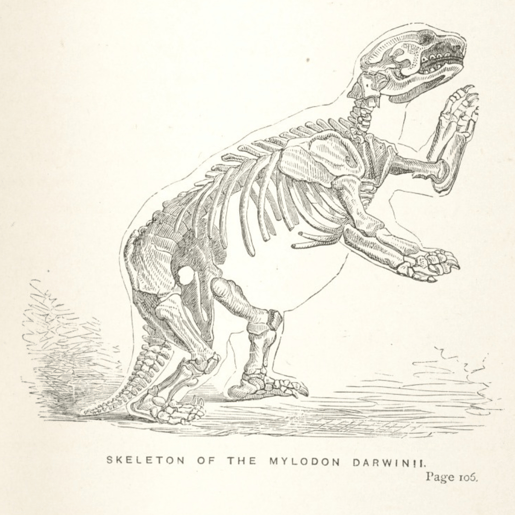

Not quite. Darwin had in fact discovered a species of ground sloth, Mylodon darwinii. Darwin ended up bringing back fossils of four species of ground sloth, but the mylodon was the only one not yet known to science.

Ten feet long and weighing somewhere between 2,200 to 4,400 pounds, the mylodon lived during the Pleistocene (between 1.8 million and 12,000 years ago) throughout South America.

Illustration from Darwin's Journals.

Illustration from Darwin's Journals.

After further analysis of the mylodon fossil, Darwin recognized that this species was related to the modern sloth, and in The Voyage of the Beagle (1839), he wrote “This wonderful relationship in the same continent between the dead and the living will, I do not doubt, hereafter throw more light on the appearance of organic beings on earth, and their disappearances from it.”

That passage was published twenty years before the publication of On the Origin of Species, but you can see that the gears in Darwin’s mind were turning. Combined with the concept of extinction, studying the relationship between fossils and modern animals helped him develop the theory of evolution, which is strongly supported by the fossil record today.

We still aren’t done studying the mylodon. We thought that ground sloths, like their modern, tree-dwelling relatives, were strict vegetarians, but recently, researchers analyzed hair samples from living and extinct species of sloths and anteaters. They found that mylodon had higher levels of nitrogen in its fur, indicating that it was omnivorous! The mylodon might have been a scavenger whose prey was killed by other animals, or it may have eaten bird eggs.

2. The Falklands wolf

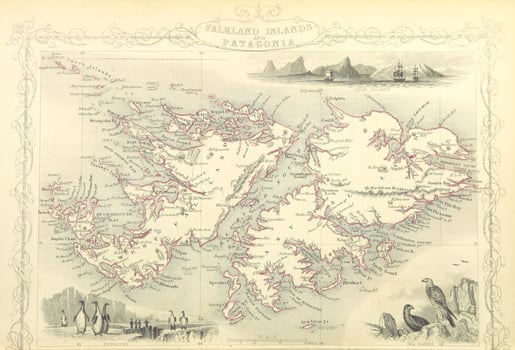

Six months after discovering fossils in Punta Alta, Darwin arrived in the Falkland Islands, a remote archipelago about 300 miles northeast of the southern tip of South America.

Map of the Falklands from The Voyages of James Cook.

Here, he met the only native land mammal on the islands: the Falklands wolf, also known as the warrah. The Falklands wolf was roughly the size of a coyote, with reddish-gray fur and an appearance somewhere between a wolf and a fox.

Despite the name, the Falklands wolf wasn’t actually a wolf—nor was it a fox or a dog. According to DNA analysis, the Falkland wolf’s closest living relative is the maned wolf—which is not actually a wolf either. The maned wolf is the only species in the genus Chrysocyon, and is related to other fox-like canids from South America.

![]() Illustration from Wikipedia Commons.

Illustration from Wikipedia Commons.

When Europeans first found the Falkland Islands, they were uninhabited. The British built a settlement in the 1700s that they soon abandoned, and Argentina had laid claim to the islands, but the same year Darwin visited, Britain regained control.

With no predators and no reason to avoid humans, Falklands wolves were friendly and unafraid of Darwin and other humans.

Darwin wrote, “The number of these animals during the past fifty years must have been greatly reduced… and it cannot, I think, be doubted, that as these islands are now being colonized, before the paper is decayed on which this animal has been figured, it will be ranked among those species which have perished from the earth.”

He was right; within four decades, the Falklands wolf was extinct. Humans hunted and poisoned the species into extinction.

The mystery of how the Falklands wolf came to live in the Falklands is one that stumped Darwin and continues to puzzle researchers today.

“As far as I am aware there is no other instance in any part of the world, of so small a mass of broken land, distant from a continent, possessing so large a quadruped peculiar to itself,” Darwin wrote.

In 2013, researchers from the University of Adelaide, Argentina, and Chile looked at genetics, fossils, and oceanographic evidence to figure out when the Falklands wolf arrived in the Falklands. They calculated through DNA that the Falklands wolf split from the mainland 16,000 years ago—about 4,000 years before humans arrived in South America.

They argue that because sea levels were lower and the islands were larger during this period, there were 20-30 kilometers of water between the islands and the mainland. This strait could have frozen over, creating an ice bridge for the Falklands wolf to cross. This icy connection to the mainland must have been brief, because it appears that other land mammals did not cross over.

In 2021, however, researchers from the University of Maine published a paper arguing that the Falklands wolf was brought over by pre-European settlers. They say that there isn’t much geological evidence for an ice bridge to the Falklands, and offer evidence of their own.

They note that there is more charcoal (perhaps from man-made fires) preserved in Falklands bogs starting in 1800 BC with a spike around 550 BC. Radio-carbon dating indicates that Falklands wolves were present on the island at the same time as the charcoal.

The researchers theorize that the Yaghan people of Tierra del Fuego in modern-day Argentina and Chile brought them over. The Yaghan, who still live in the area, were historically hunters and gatherers who traveled all over the area in canoes. This is supported by piles of bones found around the islands—mostly rockhopper penguins and southern sea lions—that could have been left by humans. In the 70s, an arrowhead was found near one such bone pile.

As we learn more about the Falklands wolf and as technology advances, maybe someday we will solve this mystery.

3. A platypus?!

When he started his voyage, Darwin was fresh from studying at Cambridge. Had he not traveled on the Beagle, his future would have been as a clergyman in the English countryside. In fact, Darwin's father, who paid for his equipment and expenses while on the Beagle, expected him to join the clergy upon his return to England. Young Darwin was passionate about studying the natural world, but he did not appear to question creationism, the leading theory of its day.

When Darwin laid eyes on a platypus, that began to change.

On the last leg of its voyage, the Beagle visited Australia for nearly two months. Darwin explored Sydney, the Blue Mountains, Hobart, New Norfolk, and King George Sound. While near Wallerawang, west of the Blue Mountains, Darwin watched rat-kangaroo and platypuses in their natural habitat, and one of his companions shot a platypus so that Darwin could study its anatomy up close. He was fascinated by the strange little creature.

Illustration from John Gould’s Mammals of Australia.

Illustration from John Gould’s Mammals of Australia.

Darwin wasn’t the only person to be amazed at the sight of a platypus. For decades, naturalists back in Europe thought them to be a hoax. At the time, famous circus owner P.T. Barnum had a “feejee mermaid” on display, which was fish skin sewn onto a taxidermied monkey, so it stood to reason that platypuses were fakes, too.

Europeans also didn’t know what to make of the platypus’s reproductive organs: though the platypus has fur and in many ways resembles other mammals, it has reproductive organs more similar to a reptile.

Even after the platypus was described, they weren’t sure how to classify it: did it lay eggs or did it give birth and nurse? The answer: both. The platypus lays her eggs in a burrow and after ten days, the baby platypuses hatch and nurse for up to four months. This fact was obscured by the fact that female platypuses don’t have nipples—instead, they secrete milk from their pores. You can see why this was difficult for Europeans to wrap their heads around!

Darwin wrote that he “had the good fortune to see several of the famous Platypus or Ornithorhynchus paradoxicus. They were diving & playing in the water; but very little of their bodies were visible, so they only appeared like so many water Rats.”

In studying the platypus and kangaroo rats, Darwin wondered why these Australian animals filled similar ecological niches as the rabbit and water rat back in England: why create different species that seemed to do the same thing? Ecological niches wouldn’t be defined for almost a hundred more years, but this line of inquiry sparked his curiosity and challenged creationism.

Darwin descendant and ecologist Chris Darwin says that the “platypus moment” marked a turning point in Darwin’s thinking as he began to realize that animals adapt to their environments.

Read more, think more

Curious about evolution? Check out our other blog posts on the topic:

Want to use this blog post in the classroom? Here are some discussion questions to get your students talking:

- How can DNA analysis support the theory of evolution?

- How did Darwin’s voyage on the Beagle develop his views?

- What are similarities and differences between the mammoth skeleton and the elephant skeleton?

- What are some animals that fill similar ecological niches? How could they have evolved independently?

Want more tools to help you teach biology? Check out Visible Body Suite, a visual guide to the life sciences.

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more awesomeness!

Are you an instructor? We have award-winning 3D products and resources for your anatomy and physiology or biology course! Learn more here.